HTML

-

深水水道是连接陆棚和深海平原的重要沉积物输送通道,是深海沉积“源—渠—汇”体系的重要组成部分[1⁃3]。深水水道中砂体和细粒沉积形成了良好的油气储盖组合,受到沉积学家和石油勘探家的广泛关注,并在东非鲁武马盆地、西非下刚果盆地、英国北海盆地、墨西哥湾盆地、巴西坎波斯盆地、中国南海琼东南盆地和西沙海槽盆地等地区发现了大型深水水道及相关沉积体的油气富集成藏[4⁃12]。

深水水道沉积演化过程中,由于海底地形坡度、重力流性质、海底底流改造作用等因素会形成复杂多变的内部结构和多期次叠置的旋回特征[10,13⁃14]。砂泥为主的水道内部结构中,富砂沉积物的分布规律十分复杂[9,15],其侧向物性变化很快,且不同旋回的含砂量变化很大,水道砂质储层分布的复杂性严重制约该类型油气藏的精细勘探和高效开发[16⁃19]。探索深水水道沉积演化及其对储层分布的控制机理具有重要的实践价值。深水水道的迁移演化是探索深水水道沉积演化的基础,加强水道迁移规律研究以及水道内部沉积结构解析,将有助于预测水道砂体内部非均质性变化,解决限制该类型油气藏精细勘探和高效开发的难题。

深水水道具有多种迁移方式[15,20⁃24]:相对连续的迁移方式包括侧向摆动迁移、垂向叠置迁移以及二者混合方式(侧向摆动叠置迁移),迁移相对连续的水道是形成复合水道的基础;不连续的迁移方式包括向下侵蚀迁移和空间跳跃迁移[1],这些迁移形成了分隔复合水道的界面,是形成深水水道体系的基础。许多研究探讨了水道迁移的控制因素[10,24⁃27],认为水道迁移受地形坡度变化、下伏岩层性质、沉积物性质及搬运速率、底流性质及方向、水道自身限制能力等多种因素共同控制,这些因素之间相互影响形成了复杂的控制体系,在不同深水环境中对水道的影响差异巨大。

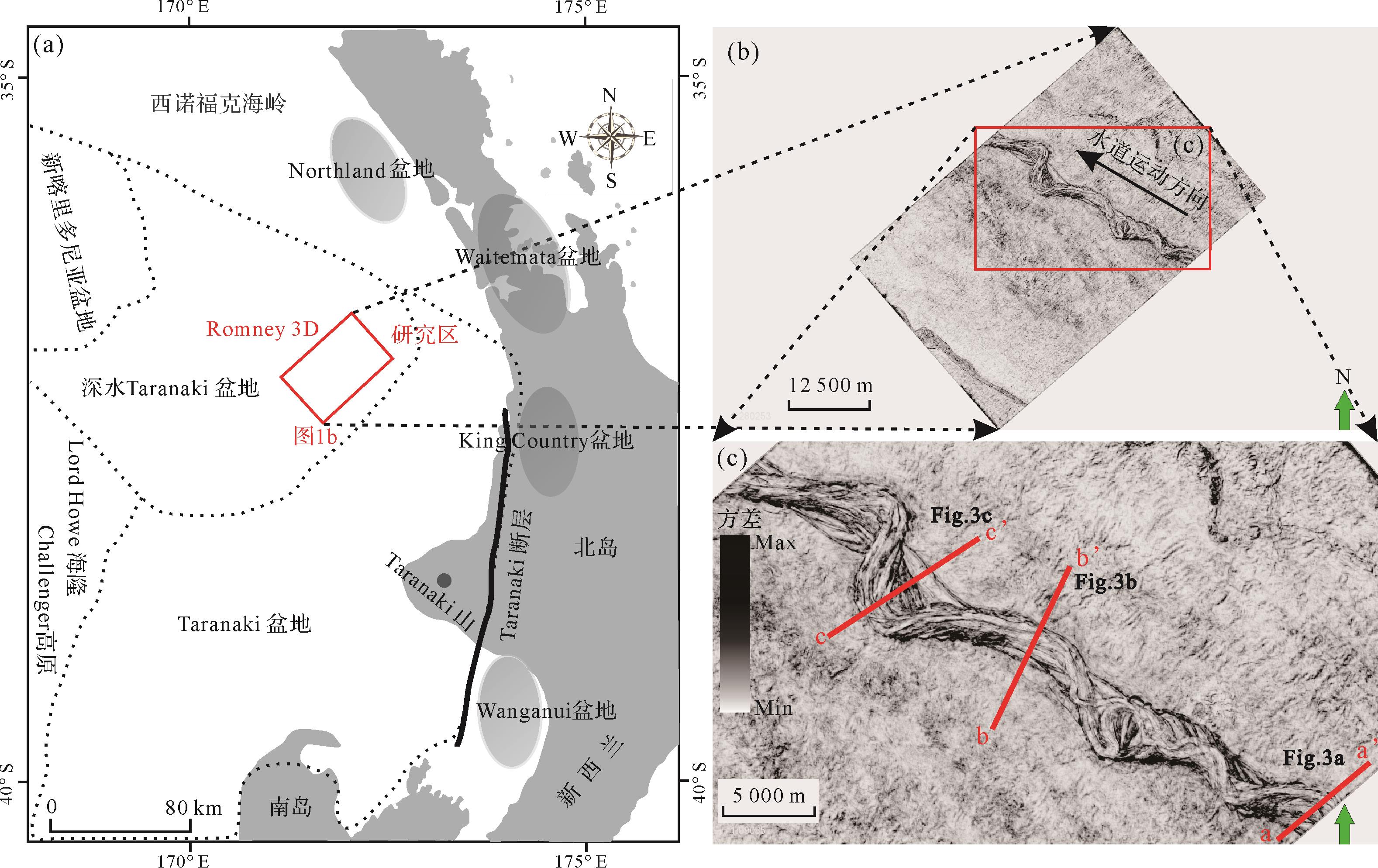

因此,笔者以新西兰深水Taranaki盆地中新世水道体系为研究对象,利用高分辨率三维地震数据,采用地震属性提取、沿层切片等多种适用于深水水道研究的地震解释技术,探究深水水道的沉积演化规律及主控因素。

-

研究区是新西兰深水Taranaki盆地(图1)的西北延伸,位于现今新喀里多尼亚海槽的东南方[28]。盆地内沉积物供给主要来自新西兰南岛北部和北岛西部[29]。盆地北部为西诺福克海岭及Northland盆地,西北部为新喀里多尼亚盆地,西南部为Lord Howe隆起及Challenger高原,南部为Taranaki盆地,东部发育一系列小盆地[30]。目前,研究区域仍属超深水前沿勘探新区,除了周边海域存在浅层大洋钻探井外无其他油气资源钻井,唯一的Romney-1井在钻探期间未发现早于中新世的岩性样品[31]。研究区内三维地震数据覆盖超过1 000 m水深的面积约1 700 km2,总体勘探程度较低[32]。

-

新西兰深水Taranaki盆地内充填了白垩纪—第四纪的沉积地层(图2),其中最老地层为晚白垩世Taniwha组的陆相层序[34],其上为分布广泛的Rakopi组陆相砂、煤系地层和North Cape组滨海沉积[35];古新世—始新世,盆内充填了Kapuni群的陆相—浅海相煤和陆源碎屑沉积[29],分别代表次生油气源和原生储集岩[36];渐新世—早中新世,盆内充填了广泛沉积的钙质泥、石灰岩和少量Ngatoro群的碎屑岩[37],指示海平面在不断上升,研究区从浅海沉积过渡为半深海沉积;中中新世,盆内充填以深海重力流和泥岩为主的碎屑沉积;晚中新世—现今,研究区海平面逐渐下降,形成以陆架—陆坡泥质沉积、陆坡重力流沉积等为主的沉积组合,盆地东北部和中部的局部地层发育火山岩和火山碎屑沉积物[29]。

Figure 2. Chronostratigraphy, generalized facies, lithology, and relative sea level relationships from N-NW to S-SE across the deep⁃water Taranaki Basin, New Zealand[33]

研究目的层段为中中新统,受澳大利亚—太平洋板块转换边界的演化(阿尔卑斯断裂)影响,中中新世盆内陆源碎屑沉积物供给逐渐增加,陆架边缘向西外扩[38],结束了先前不断上升的海平面变化趋势,海退层序开始,研究区开始发育大规模深水水道等重力流沉积。

-

本文研究数据为新西兰Anadarko公司于2011年10月23日至12月6日期间获得的三维地震勘探数据,并于2013年2月由ION地球物理公司所处理(NZP&M石油报告可从www.nzpam.govt.nz获取)。该三维地震数据体的垂直采样间隔为4 ms (TWT),处理面元为25 m×25 m,主频近35 Hz,地震波传播速度约为1 850 m/s,故垂直分辨率约为13 m[39],能够满足此次研究的需要。

本研究利用沿层切片及地震属性提取等地震解释技术,追踪并解释了目的层段顶、底部连续性较好的地震同相轴,在顶、底界之间生成若干切片,并顺层提取地震属性(如RMS振幅属性、方差属性等)生成属性平面图像。综合不同切片处剖面地震反射特征及平面形态变化特征,选定底界面之上40 ms、140 ms、220 ms及280 ms位置处的切片(记作Slice1-5,即S1~S5)作为本次研究的典型切片。方差属性能清晰识别深水水道与周围远洋沉积边界,凭借沿层方差切片成像,刻画水道的整体轮廓。由于本次研究缺少相关钻测井资料,但结合现有研究,振幅属性能较好反映水道充填沉积物的特征——振幅较强时反映偏砂相沉积,振幅较弱时反映偏泥相沉积[40],故借此可分析目标水道体系内充填沉积物性质,进而分析其内部流体特征。剖析不同区域的典型地震剖面,根据识别出的复合水道侵蚀界面,划分水道发育期次,描述水道沉积特征。利用地震剖面与沿层属性切片成像的交互显示,刻画各期复合水道平面形态特征,探究其沉积演化过程及主控因素。

1.1. 研究区概况

1.2. 地层特征

1.3. 研究数据及方法

-

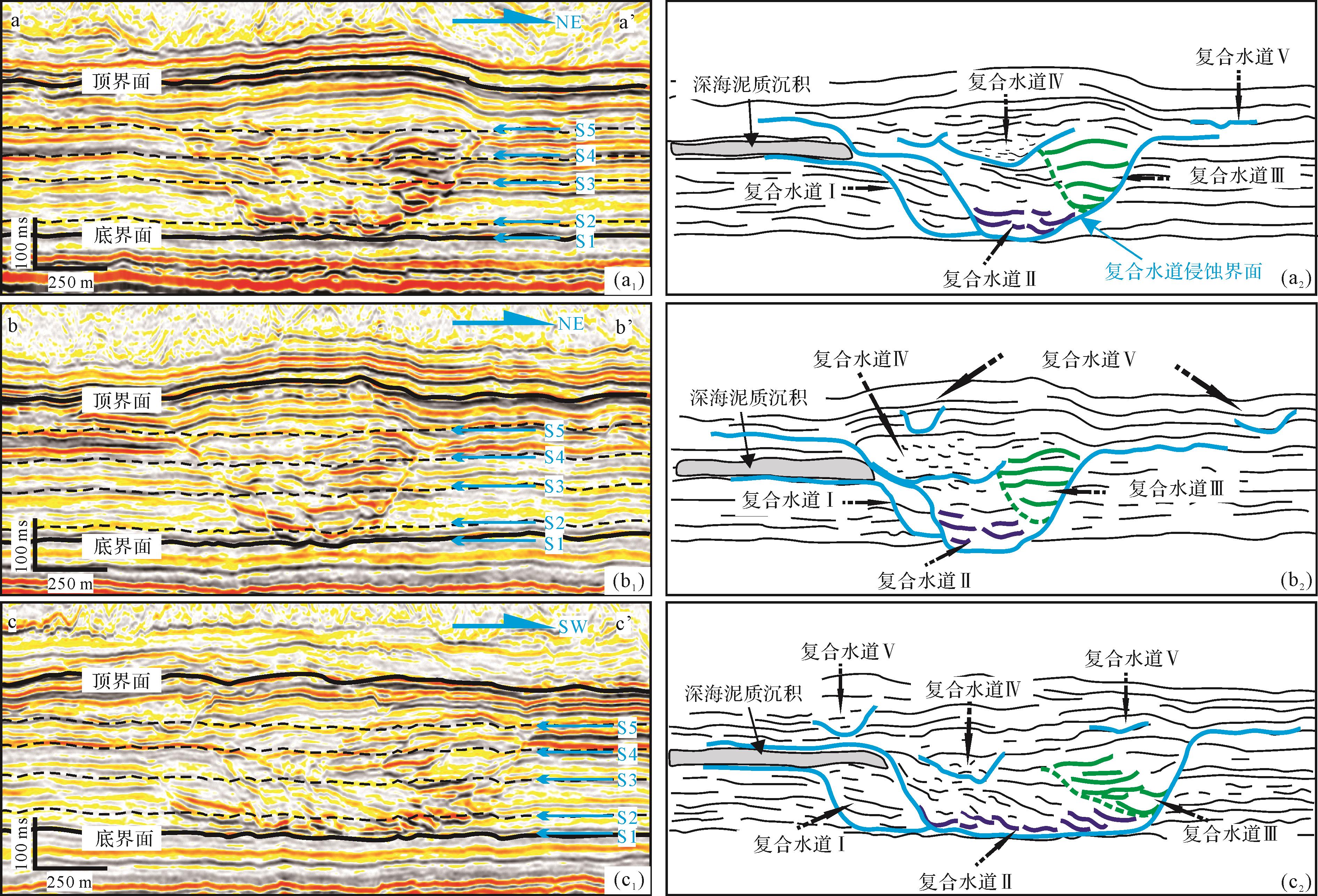

新西兰深水Taranaki盆地中中新统发育一套大型水道体系,分别在其上、中、下游区域各生成一条典型地震剖面,剖面中可识别水道内部结构,并观察到存在多期次切割—旋回叠置(图1c、图3)。

Figure 3. Developmental period division of the deep⁃water channel (profile locations are shown in Fig.1c)

根据地震剖面中识别出的复合水道侵蚀界面,目标水道体系的发育可划分为5期,即残余部分沉积结构的复合水道Ⅰ、横向迁移运动的复合水道Ⅱ、垂向叠置运动的复合水道Ⅲ、富泥杂乱充填的复合水道Ⅳ及零散分布的复合水道Ⅴ(图3)。复合水道Ⅰ为早期水道的残留部分,其顶底存在明显侵蚀特征。复合水道Ⅱ以侧向迁移为主,垂向上基本无运动。复合水道Ⅲ以垂向叠置为主,伴随着水道宽度增加和小幅度的偏移。复合水道Ⅳ与前3期水道存在差异,水道内表现为弱反射侵蚀—充填结构,且水道叠置和迁移特征不明显,与早期水道发育位置相比发生明显的深泓跳跃(图3)。复合水道Ⅴ发育多条细小孤立分散水道,其流动轨迹已超出下切谷围限。

-

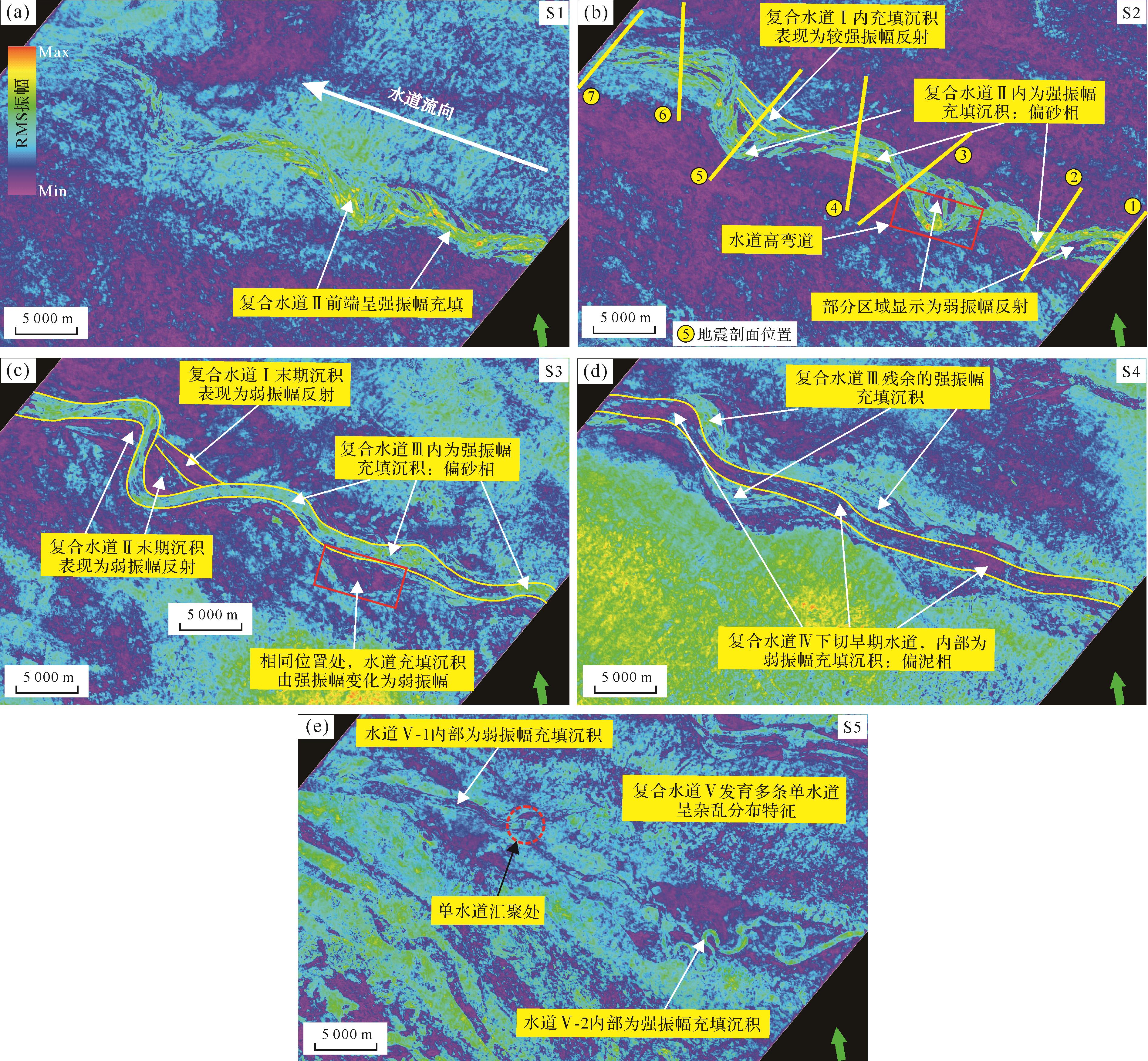

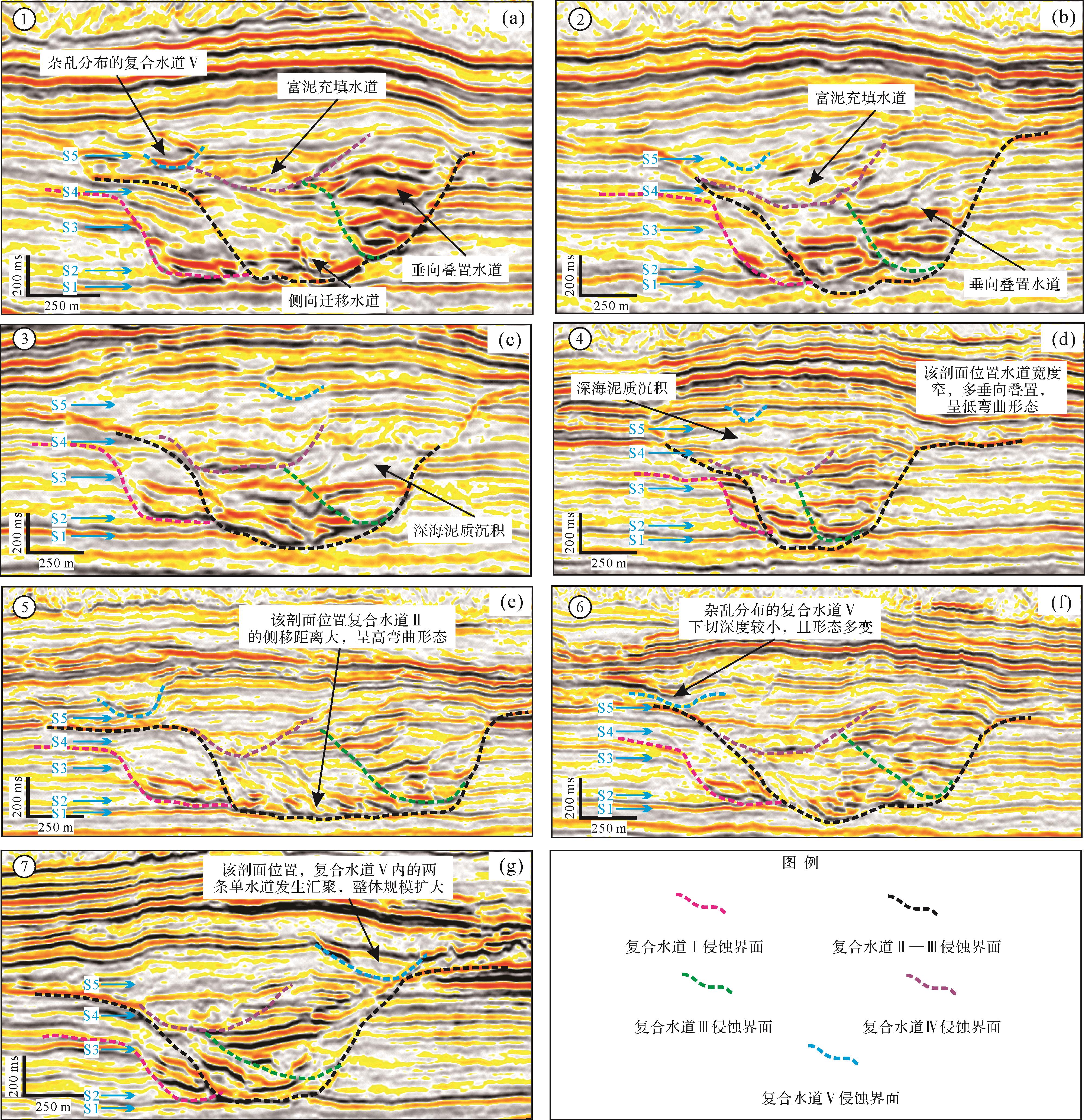

各期次复合水道的平面形态差异较大,内部单水道的迁移方式也有显著不同。结合水道的沿层属性切片(图4,5)及不同区域的典型地震剖面(图6),探究深水水道体系的平面形态演化过程(图4~7)。

Figure 4. Horizontal slices of the variance attributes of the deep⁃water channel in the study area (see Fig.3 for location)

Figure 5. Horizontal slices of the Root⁃Mean⁃Square (RMS) amplitude attribute of the deep⁃water channel in the study area (see Fig.3 for location)

-

复合水道Ⅰ遭后期水道破坏,目前仅残存部分结构(图6)。通过方差属性分析(图4)和残存水道拼接,恢复了复合水道Ⅰ未破坏前的平面形态,结果显示复合水道Ⅰ平面形态相对顺直且宽度变化不大(图7a)。

-

复合水道Ⅱ经历了对复合水道Ⅰ的侵蚀,深泓深度稳定后水道以侧向迁移摆动为主,其宽度不断增加,整体呈高弯曲形态(图4~7)。随着单水道深泓线的横向摆动,水道弯曲度逐渐增大,在方差属性切片中可识别出多期单水道侧向迁移(图4b)。尽管复合水道Ⅱ以侧向迁移为主,但研究区东部局部地区也存在单水道顺水流方向的迁移运动(图4b)。

-

复合水道Ⅲ改变了先前单水道侧向迁移的方式,整体以垂向加积叠置为主(图4c),在水道高弯道处发生截弯取直作用,形成废弃水道,而单水道宽度也由下向上逐渐增加,且弯曲度逐渐减小(图6、图7c)。

-

复合水道Ⅳ与前3期强反射复合水道不同,其内部充填呈弱振幅反射,代表水道内的充填沉积为偏泥相(图5),且其平面形态相对顺直(图7d)。复合水道Ⅲ消亡后,其早期形成的沉积空间未被完全填平(图3),当新的低密度重力流活动时,重力流仍优先流经先存的低洼带形成新的沉积物通道。

-

复合水道Ⅴ包括多条零散的细小单水道,发育于复合水道Ⅳ之上的深海泥质沉积。复合水道Ⅴ整体不受先前沉积空间限制,单水道呈分布杂乱且形态各异的特征。方差属性切片中识别出两条形态较清晰且运动方向不同的水道:水道Ⅴ-1呈相对顺直的平面形态,水道Ⅴ-2呈高弯曲平面形态,且两条单水道在水道体系的下游发生汇聚(图7e)。

3.1. 复合水道Ⅰ平面形态

3.2. 复合水道Ⅱ平面形态

3.3. 复合水道Ⅲ平面形态

3.4. 复合水道Ⅳ的平面形态

3.5. 复合水道Ⅴ的平面形态

-

深水水道的沉积演化一直是深水沉积领域内研究的重难点。McHargue et al.[41]提出水道—堤岸复合体存在4个演化阶段,即水道下切侵蚀、低加积速度下以侧向迁移为主的水道叠置运动、中等加积速度下的无序演化及高加积速度下的有序演化。结合前文对目标水道体系发育期次及平面形态的分析,认为前4期复合水道是有序的演化过程,而复合水道Ⅴ则是无序演化。无论是有序或无序的水道演化,各期次复合水道的演化会经历初期下切侵蚀、中期充填沉积及末期填平消亡等3个阶段(图8)。

复合水道Ⅰ遭受后期复合水道Ⅱ的侵蚀破坏,仅残余部分沉积结构,因此无法了解其具体的运动过程。通过识别残余沉积结构的地震反射特征,复合水道Ⅰ在初期下切侵蚀阶段主要表现为水道深度的加深和宽度的增大,中期充填沉积阶段则以底部强振幅沉积、顶部杂乱弱振幅沉积为主要特征。当重力流活动停歇时,水道顶部逐渐沉积弱反射深海泥质沉积。依据复合水道Ⅰ的侵蚀边界与深海泥质充填之间的位置关系(图3,7),水道初期下切侵蚀阶段形成的沉积空间已被填平,这也标志着复合水道Ⅰ的消亡。

复合水道Ⅱ和Ⅲ是演化过程最为复杂的两个期次,其初期下切侵蚀阶段与复合水道Ⅰ类似,主要差异体现在中期充填沉积阶段。复合水道Ⅱ以侧向迁移运动为特征,在中上游区域水道的侧向移动距离较短、平面弯曲程度较小,而在下游区域内水道侧向移动距离较长且平面形态弯曲度增大(图3~5)。复合水道Ⅲ则是以垂向叠置运动为特征,在中上游区域内水道表现为垂向叠置(图3a,b),而下游区域的水道则表现为垂向偏移—叠置运动,即存在向复合水道轴部方向偏移的趋势(图3c)。末期填平消亡阶段,水道以充填深海泥质沉积为特征,但由于复合水道Ⅱ和Ⅲ在初期下切侵蚀阶段形成沉积空间规模较大,末期填平消亡阶段所充填的沉积物无法填平该沉积空间,造成目标水道体系仍具有负地形特征。

随后发育的复合水道Ⅳ,将继续沿着负地形运动。据地震剖面中识别出的水道侵蚀界面(图3),复合水道Ⅳ仍具备下切侵蚀能力。复合水道Ⅳ的内部充填沉积在RMS振幅属性沿层切片呈弱振幅反射特征,代表其内部充填沉积物多为偏泥相(图5d)。复合水道Ⅳ发育至末期填平消亡阶段,大量深海泥质沉积沉降,将早期形成的沉积空间填平,这也标志着目标水道体系负地形特征的消失。当新一期重力流活动发育时,水道发育至最后期次——复合水道Ⅴ。由于负地形的消失,复合水道Ⅴ的运动范围相较前4期复合水道有所增大,并发育多条分布杂乱、形态各异的单水道(图4,5)。这些单水道虽下切深度较浅、宽度较窄,整体规模较小,但仍表明单水道在发育初期具备下切侵蚀的能力。然而,受地震分辨率影响,对单水道的内部结构特征难以进行刻画,但能够观察到单水道的剖面形态多呈“V”型或“U”型(图3)。相较早期复合水道而言,这些单水道的形成意味着此时期重力流活动偏弱,会因后续重力流沉积物供给的不足而逐渐被深海泥质沉积披覆,进而消亡。

-

复合水道Ⅰ为目标水道体系中发育最早的一期水道,在复合水道Ⅰ进入消亡阶段后,顶部沉积了较厚层的深海泥质沉积物(图3,8),充填了先前下切侵蚀形成的负地形。因此,复合水道Ⅰ对后期水道发育环境的限制程度基本未造成影响。

后期发育的复合水道Ⅱ对早期复合水道Ⅰ产生强烈的侵蚀破坏,在地震剖面中仅能识别出复合水道Ⅰ的部分残余结构,复合水道Ⅰ、Ⅱ之间也可识别出明显的侵蚀界面(图3,8)。由于复合水道Ⅱ和Ⅲ的强下切侵蚀所形成的大规模沉积空间,使水道整体处于强限制性环境中,重力流被限制在水道内部,流体溢岸沉积等基本不发育。

复合水道Ⅱ和Ⅲ消亡之后,早期形成的沉积空间并没有充填足够的沉积物使其被完全填平(图3、8),目标水道体系仍具有负地形特征,其发育环境的限制性仅由强变弱。负地形的存在使后期的复合水道Ⅳ继续沿着低洼地带运动,根据RMS振幅属性沿层切片,推测复合水道Ⅳ内重力流沉积物多为偏泥相,并具有一定的下切侵蚀强度,在地震剖面中也能识别出复合水道Ⅳ的侵蚀界面(图3)。复合水道Ⅳ消亡后,在其顶部识别出的大量深海泥质沉积已将早期沉积空间填平,使目标水道体系的发育环境由限制性转变为非限制性。随后的复合水道Ⅴ发育在非限制性环境中,新一期重力流的横向活动范围大大增加,形成了多条下切深度相对较浅的单水道,并具有杂乱分布、平面形态各异的特征。

-

深水水道发育过程中,沉积物重力流会对水道的沉积演化、几何形态变化产生重要影响,重力流规模及能量的变化会造成水道的规模及形态差异。本文目标水道体系受到重力流规模及能量变化影响,主要体现在两个方面:一是在复合水道Ⅱ和Ⅲ的发育过程中,水道高弯道位置处发生了截弯取直作用,其平面形态由高弯曲转变为相对顺直;二是5期复合水道的规模存在较大差异。

前文在刻画水道平面形态变化时,发现在复合水道Ⅱ和Ⅲ的发育过程中,一个高弯度的水道弯道处发生截弯取直作用,原先的高弯道被废弃(图4,5)。结合前人研究成果,造成该现象的原因除了受水道弯道自身弯曲度过大影响之外,重力流规模及能量在高弯道处发生突然变化可能也是造成该现象的原因[42]。

目标水道体系在发育过程中所形成的5期复合水道,其规模由大至小分别为:复合水道Ⅱ、复合水道Ⅲ、复合水道Ⅰ、复合水道Ⅳ、复合水道Ⅴ(图3)。各期次复合水道的沉积演化过程可分为初期下切侵蚀、中期充填沉积及末期填平消亡等3个阶段(图8)。深水水道初期下切侵蚀阶段,往往是重力流最活跃的时期,复合水道内物源供给充足,重力流规模及能量均处于最大值,其内部流体以下切侵蚀作用为主,可强烈破坏下伏地层,此阶段重力流可能发生过路不留;而水道发育至中期充填沉积及末期填平消亡等阶段,重力流的规模及能量减弱,从而导致水道内粗粒沉积物开始沉降,直至水道顶部沉积深海泥质沉积物而消亡。重力流规模及能量的变化可能是导致不同期次复合水道宽度、下切深度等差异的主要因素。重力流的规模大、能量强时,此时会发育Ⅰ、Ⅱ期复合水道,复合水道的下切深度及宽度较大,易形成强限制性的水道发育环境;当重力流对下伏地层的侵蚀能力变弱时,此时会发育Ⅲ、Ⅳ期复合水道,水道发育环境的限制性由强变弱,以加积作用为主,水道内部碎屑物质开始大量沉降;当重力流活动发育在非限制环境中时,此时会发育Ⅴ期复合水道,由于水道的运动范围不受限制,所形成的多条单水道在空间上分布较为杂乱,并且不同单水道间的形态差异较大。

5.1. 早期水道结构对后期水道发育环境限制程度的影响

5.2. 重力流规模及能量的变化

-

(1) 根据地震剖面中识别出的复合水道侵蚀界面,目标水道体系可划分为5个发育期次,即残余部分结构的复合水道Ⅰ、侧向摆动的复合水道Ⅱ、垂向叠置的复合水道Ⅲ、富泥充填的复合水道Ⅳ及零散分布的复合水道Ⅴ。

(2) 通过沿层属性切片及地震剖面分析,复合水道Ⅰ、Ⅳ整体呈相对顺直的平面形态;复合水道Ⅱ多为横向迁移运动,并表现出高弯曲的平面形态;复合水道Ⅲ多为垂向叠置运动,水道依旧表现为弯曲平面形态;复合水道Ⅴ发育多条零散的单水道,空间上分布零散且形态各异。

(3) 各期次复合水道的沉积演化过程可划分为3个阶段,即水道的初期下切侵蚀、中期充填沉积及末期填平消亡。复合水道在初期下切侵蚀阶段表现为水道下切深度增大及宽度的增加,末期填平消亡阶段表现为深海泥质沉积的沉降,但在中期充填沉积阶段各期次复合水道的沉积特征差异最大。

(4) 深水水道沉积演化过程受多种因素的综合控制。早期水道沉积结构会控制后期水道发育环境的限制性,复合水道Ⅰ~Ⅳ整体处于限制性环境中,其演化是一个有序的过程,而复合水道Ⅴ处于非限制性环境中,经历了一个无序的演化过程。另外,重力流规模及能量的变化会影响各期次复合水道的发育规模。

DownLoad:

DownLoad: