HTML

-

海洋硬底群落是生态学研究中的重要资源,其中的附生生物或结壳(epibionts或encrusters),是附着或包裹在宿主(host)表面的生物,两者的类型、多样性和丰度、组合型式等都是海底底栖群落的重要特征,可部分反映底栖生态系统[1⁃8]。在地质历史中,它们的特征及组合是原位保存的古生态系统研究的重要材料,在不同的地质时期都存在相关研究[3,9⁃15]。对附生生物来说,宿主的类型多样,包括生物壳体和骨骼(如腕足类、双壳类、珊瑚等)及礁碱木材等,常作为附生生物的硬质基底。腕足动物的壳体是一种常见的宿主,因其易化石化的特点,在各个地质时代都十分普遍,是研究海底底栖群落中宿主与附生生物之间关系及其古生态意义的理想生物基质[5,14,16]。

海洋附生生物对水深、沉积环境、基质类型、含氧量和生产力等环境参数的变化高度敏感[6,17⁃23]。此外,附生生物在寄主壳体上的位置分布能够提供多种古生态信息。附生生物在宿主上的分布常常是有规律可循的,或者选择性地附着在宿主上,因此,腕足类作为最常见的宿主,其壳体上不同区域的附生生物分布存在明显差异,对不同腕足类壳上的结壳生物分布的统计分析,可以获得诸如寄主的生活状态、附生生物与寄主之间的关系,以及古生态和古环境等方面的重要信息[14⁃15,24⁃25]。

泥盆纪中晚期的海洋生态系统及古环境都发生了重要的改变[26⁃28],其中的弗拉斯—法门期(Frasnian-Famennian,F-F)生物危机是显生宙期间的“五大”灭绝事件之一[29⁃33],在此期间的海洋生态系统,尤其是浅水动物群和后生动物礁受到了严重的影响[34]。此次事件中,75%的腕足动物属灭绝[35],但对腕足动物结壳生物群的影响尚不清楚。

四川龙门山地区发育完整的中晚泥盆世地层,产出丰富的腕足动物化石[36],本文主要对吉维特期—法门期地层中的腕足类宿主及其结壳生物的关系开展工作,重点研究了7种腕足动物的附生生物分布规律,为F-F生物危机期间古海洋生态环境的变化提供一定的证据。

-

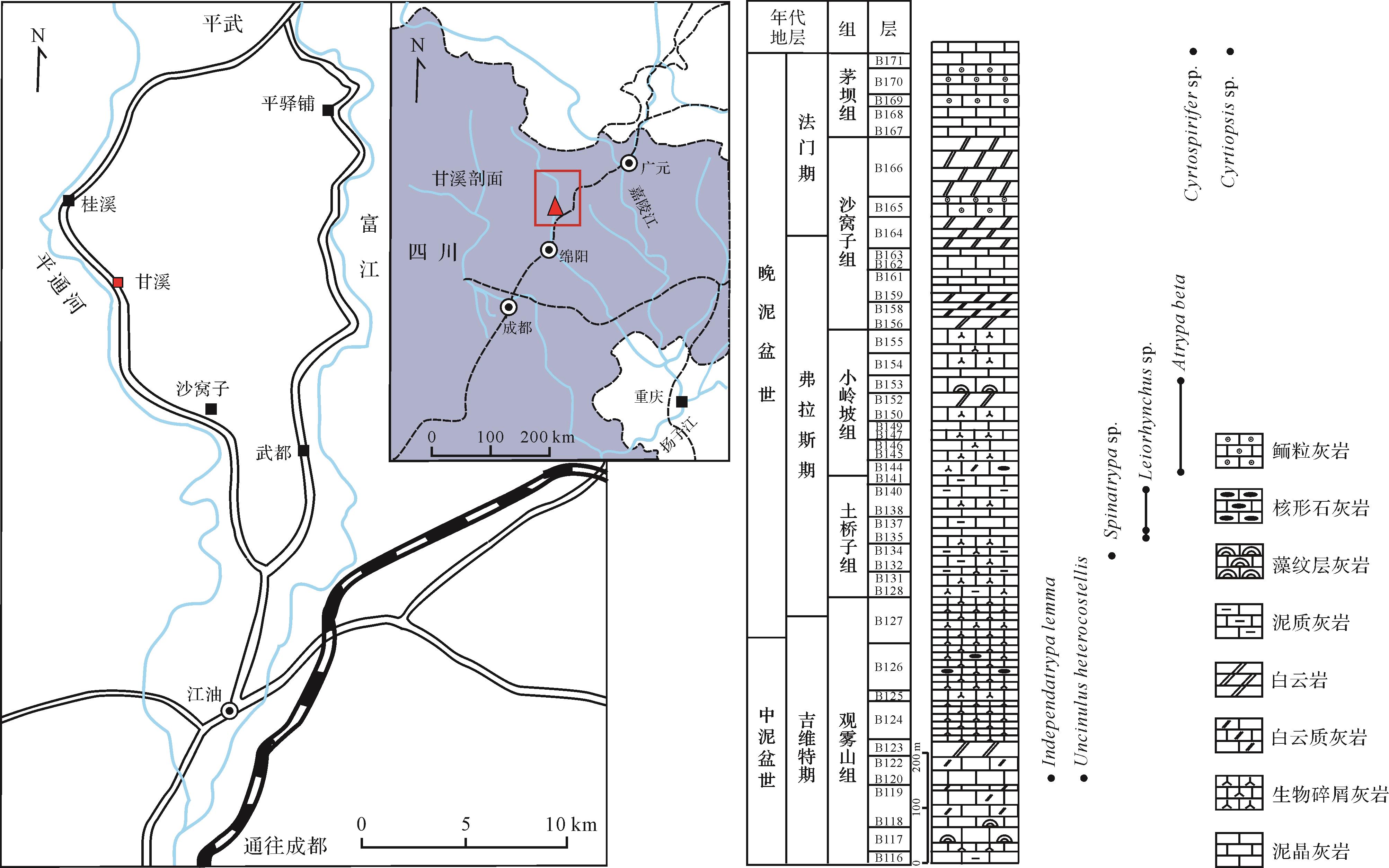

本文研究的材料采自四川省江油市北川县桂溪乡的甘溪剖面(31°54.302′ N,104°41.643′ E),位于四川省中部,属于上扬子板块西北缘龙门山地区[37]。该剖面泥盆系沿平通河展布,地层出露较好,是中国最典型的海相泥盆纪剖面之一(图1)。

Figure 1. Location map and stratigraphic column of the Ganxi section, Longmenshan area, central Sichuan (modified from Li et al.[37]) and the distribution of key brachiopods in this section

研究的化石主要来自吉维特期—法门期的地层,厚达1 000 m,自下而上依次为观雾山组、土桥子组、小岭坡组、沙窝子组以及茅坝组[36,38⁃39],各组之间均为整合接触(图1)。观雾山组主要由泥晶灰岩、生屑灰岩、白云质灰岩和白云岩组成,含有丰富的化石,如珊瑚、层孔虫、苔藓动物和腕足动物,时代为吉维特晚期。土桥子组为弗拉斯早期沉积,由泥晶灰岩和泥质灰岩组成,上覆地层为弗拉斯中期的小岭坡组,由生物碎屑灰岩和藻灰岩组成,底部为厚层的核形石泥晶灰岩,顶部为厚层的钙质白云岩。沙窝子组为弗拉斯晚期—法门早期沉积,中下部为薄层灰岩,其余以白云岩为主,化石较少。茅坝组为法门期沉积,以鲕粒灰岩为主,常含生物碎屑灰岩和层状藻灰岩。

本研究共采集了3 067枚腕足类壳体,挑选了其中具有附生生物的618枚标本作为统计对象。这些宿主腕足类经鉴定为7个种(包括未定种),归入7个属,包括Independatrypa lemma,Uncinulusheterocostellis, Spinatrypina sp.,Leiorhynchus sp.,Atrypa beta,Cyrtiopsis sp.以及Cyrtospirifer sp.。其中,Independatrypa lemma和Uncinulus heterocostellis主要产于吉维特期观雾山组B120层,Spinatrypa sp.则大量产出于弗拉斯期土桥子组的B133层,Leiorhynchus sp.产于土桥子组B135、B136、B140层。Atrypa beta大量出现在弗拉斯期小岭坡组B143和B153层。Cyrtospirifer sp.和Cyrtiopsis sp.来自法门期的茅坝组B173层(图2)。

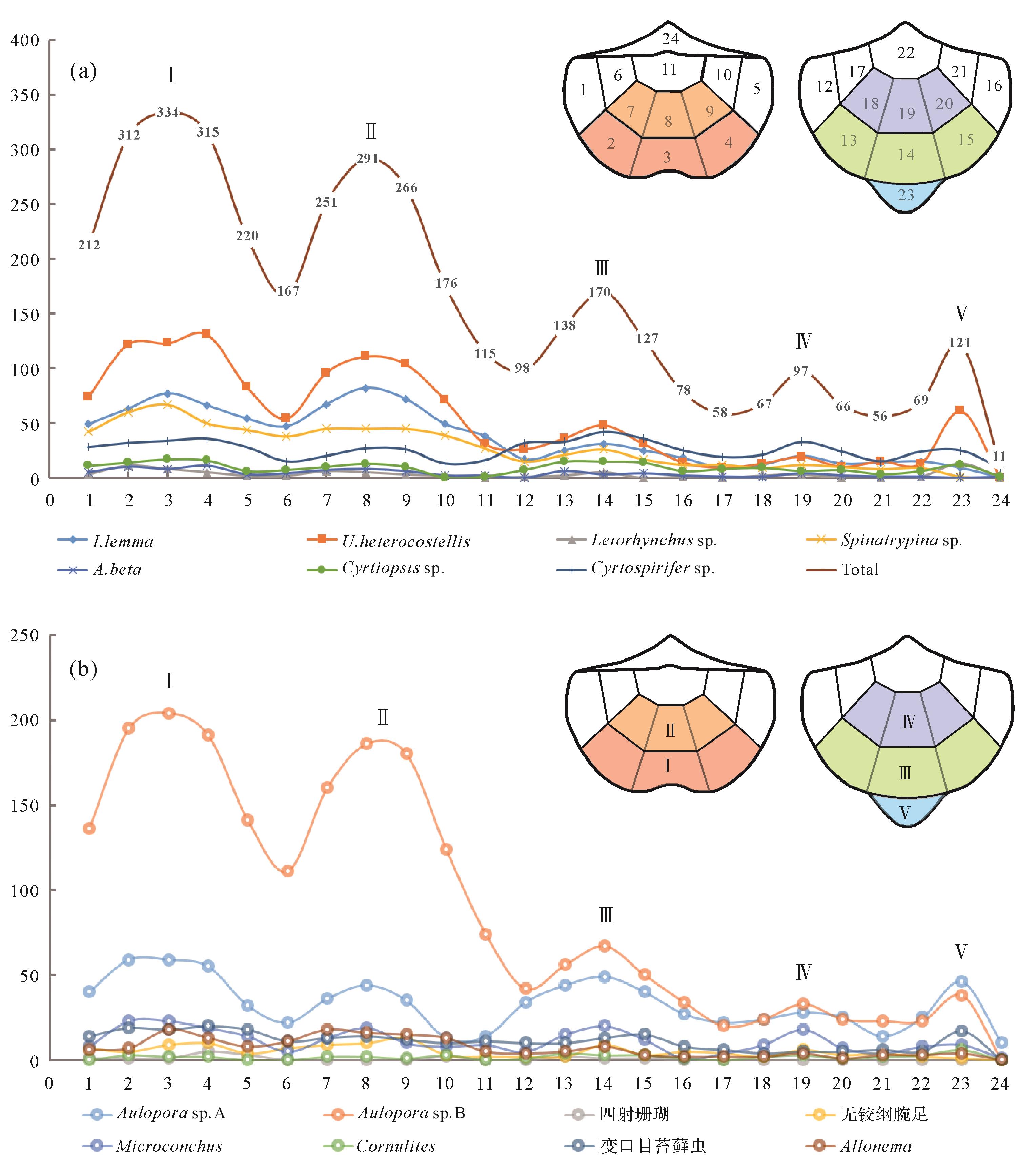

Figure 2. (a) Brachiopod brachial and (b) pedicle valves with particular sectors for the encruster abundance; distributional patterns indicated and numbered (after Chang et al.[25])

-

采集的3 067个腕足类标本,首先需要使用清水及细毛刷清理掉表面泥垢,然后用超声波清洗机(60 Hz,60 min)对每个标本进一步清洗。使用放大镜进行筛选,选出具有附生生物的腕足类标本,而后使用双目体式显微镜(10~100x 放大倍数)对所选标本的附生生物进行详细的统计分析。本研究使用的统计方法是在石和[40]和Zatoń et al.[15]的基础上修改的。除石燕贝类,其他腕足动物壳的背壳和腹壳分别分为11和12个分区(图2)。但是对于石燕贝类,即Cyrtospirifer sp.和Cyrtiopsis sp.,其突出的喙使得铰合面增大,因此较其他种类多出一个分区(图2b)。每个腕足物种的附生生物分布、附生生物在每个壳体上的取向以及分区位置都以表格形式统计。由于附生生物大多会从一个分区扩展到相邻分区,因此在统计过程中每个分区的附生生物都被记录为该附生生物的一个“个体”。另一方面,对于个体非常小的Microconchus,一个分区可能有数个个体,需要把其中附生生物的个体数量全部记录下来。根据附生类群的分区规律,分析其与腕足类寄主之间的关系,以及附生生物对寄主的特定位置有无偏好。

-

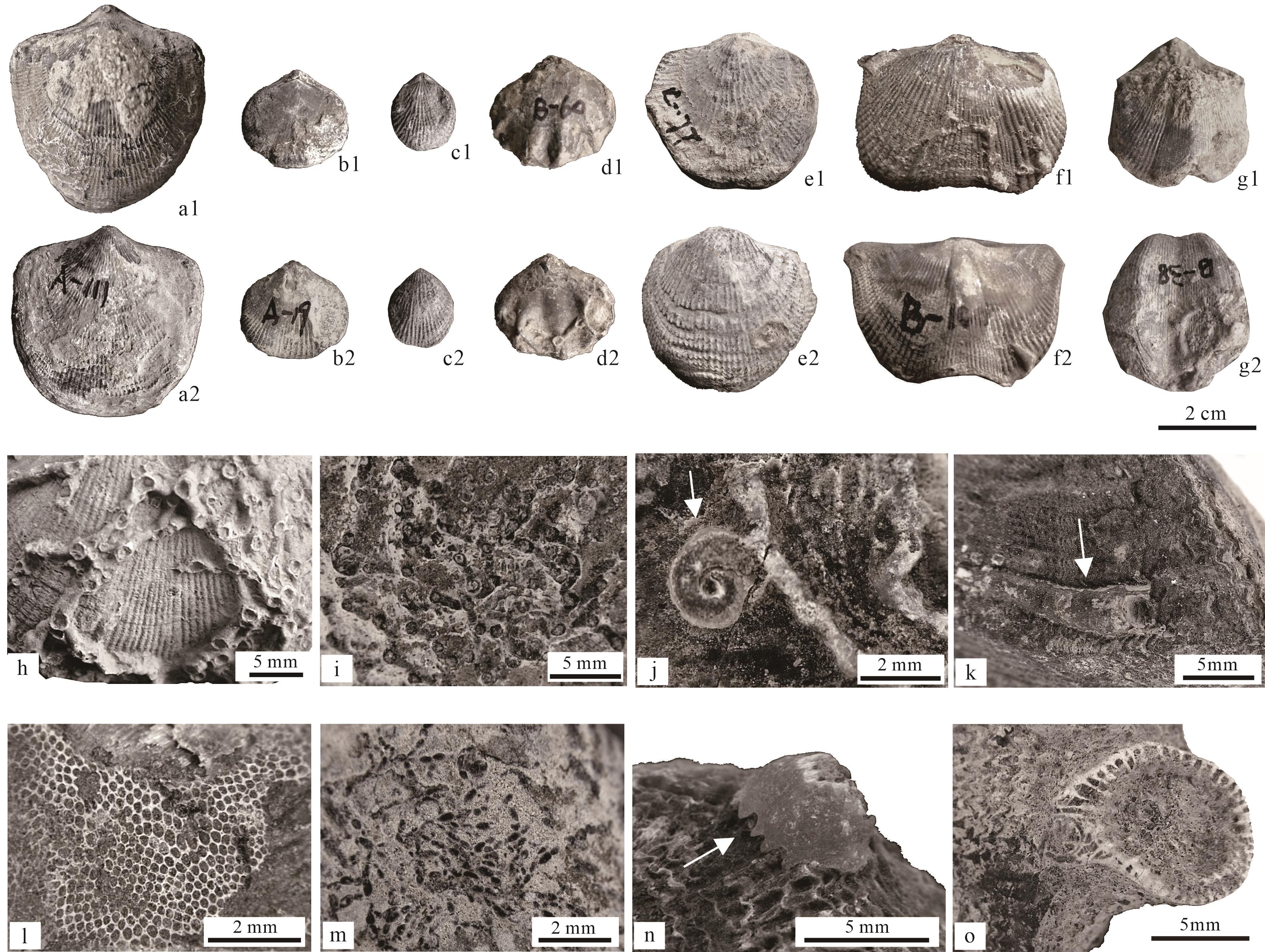

本研究中被结壳的腕足动物标本鉴定为7种:Independatrypa lemma,Uncinulusheterocostellis,Spina⁃ trypina sp.,Leiorhynchus sp.,Atrypa beta,Cyrtiopsis sp.和Cyrtospirifer sp.(图2)。壳体上的附生生物类群可分为8类,详述如下(图3)。

横板珊瑚类Aulopora Goldfuss,1826:是一类在腕足动物上常见的附生生物[1,3,8,41]。在本研究中,Aulopora由两个未定种组成,Aulopora sp.A和Aulopora sp.B,前者具有较大的直径和较厚的外壁,通常具有明显的锥形或烟斗形萼部,后者具桶形萼部且萼部之间充满泥质。

多毛类管虫Microconchus Murchison,1839:其特征是个体微小,且具有螺旋盘绕的方解石管,在某些类型中螺旋形管可能会展开[42⁃44]。本研究中的Microconchus个体微小(0.8~3 mm),完全螺旋,具中等厚度的虫管壁,生长线光滑或微弱。

多毛类管虫Cornulites Schtotheim,1820[45⁃46]:常附着在无脊椎动物宿主的外壳上。本研究中,Cornulites具有5~9 mm长的锥形钙质管,其横截面为圆形。在幼年阶段,通常虫管外壁光滑,但在个体发育后期阶段会被环或脊装饰。

苔藓虫:应属于变口目苔藓虫类(Trepostomata Ulrich,1882),不同寄主上的苔藓虫外部特征非常相似,尽管不能鉴定,但很可能为同一种,以薄片状为主,虫室微小(直径0.1~0.3 mm),且为椭圆或多边形。

微体疑源类Allonema Ulrich & Bassler,1904:是小型的方解石质硬体生物,常见于中古生代—晚古生代,特别是在泥盆纪分布十分广泛[47⁃49]。该属曾被认为是苔藓虫[50],随后经过一系列研究,认为其属于微体疑源类[47⁃48]。Allonema个体微小,由分支或不分支的体管组成,体管被分隔成不同的囊泡。囊泡多呈椭圆形,通常排列成单排[51]。

无铰纲腕足类Petrocrania Raymond,1911[24]:壳体小,外形宽卵形—近圆形,背壳凸出,喙位于中心略靠后,向后倾斜,表面有许多同心的、不规则的生长线,通常与寄主的表面纹饰一致。腹壳附着在宿主上,可能无法观察到。

小型单体四射珊瑚:偶尔也会作为腕足动物的附生生物出现。这些单体珊瑚个体小,直径小于1 mm,萼部常被泥质充填,偶见隔壁,常缺乏鳞板,很难将其划分至科以下的分类单位。

-

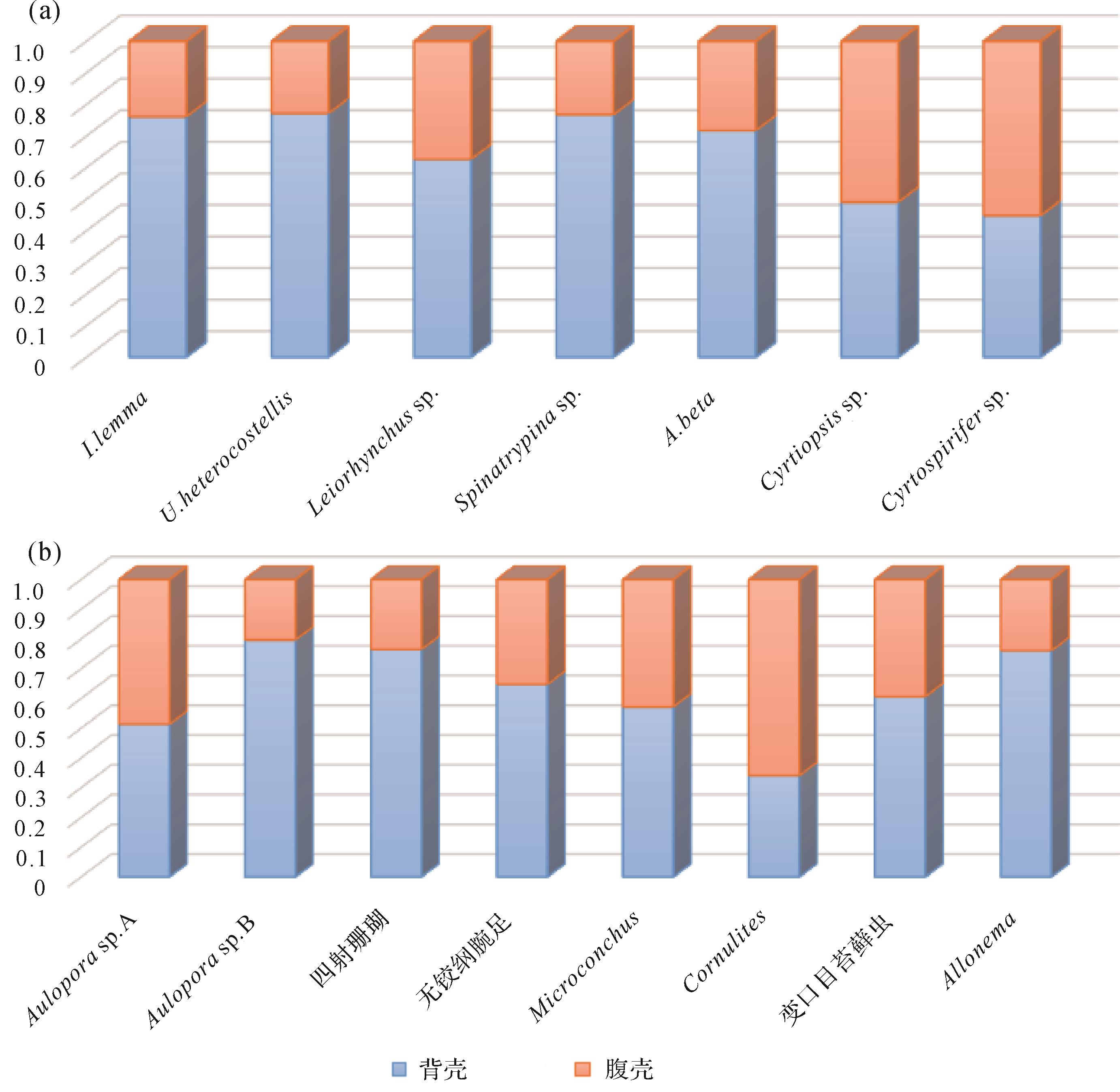

附生生物附着生活在宿主的背壳或腹壳上,具有一定的生态意义。统计结果显示,选择附着在背壳或者腹壳存在显著差异(表1、图4a)。大多数附生生物附着在背壳(51.3%~79.7%),少数在腹壳(20.3%~48.7%),而附生生物Cornulites例外,65.9%的Cornulites个体附着在宿主的腹壳上。另一方面,对不同种类的腕足类宿主进行分析,也有选择性差异,其中宿主I.lemma、U.heterocostellis、Spinatrypina sp.、Leiorhynchus sp.和A.beta,大多数结壳生物都附着在背壳上。相反,对于宿主Cyrtiopsis sp.和Cyrtospirifer sp.,结壳生物更喜欢附着在它们的腹壳上,前者腹壳上的结壳数量占比为50.9%,后者为55.1%(表2、图4b)。

腕足种类 背壳上附生生物数量 腹壳上附生生物数量 总数 背壳上附生生物占比/% 腹壳上附生生物占比/% Independatrypa lemma 664 208 872 76.15 23.85 Uncinulusheterocostellis 1 000 295 1 295 77.22 22.78 Leiorhynchus sp. 47 28 75 62.67 37.33 Spinatrypina sp. 502 152 654 76.76 23.24 Atrypabeta 66 26 92 71.74 28.26 Cyrtiopsis sp. 105 109 214 49.07 50.93 Cyrtospirifer sp. 275 338 613 44.86 55.14

Figure 4. The percentage of epibionts on two valves in: (a) epibiont taxa and (b) brachiopod species

附生生物种类 背壳上附生生物数量 腹壳上附生生物数量 总数 背壳上附生生物占比/% 腹壳上附生生物占比/% Aulopora sp.A 409 388 797 51.32 48.68 Aulopora sp.B 1 702 434 2 136 79.68 20.32 四射珊瑚 13 4 17 76.47 23.53 无铰纲腕足 79 43 122 64.75 35.25 Microconchus 151 113 264 57.20 42.80 Cornulites 15 29 44 34.09 65.91 变口目苔藓虫 160 104 264 60.61 39.39 Allonema 130 41 171 76.02 23.98 -

附生生物空间分布的分析结果表明,腕足类宿主外壳的不同分区之间存在显著差异(图5、附表1,2)。按照不同类群的腕足类宿主及不同类群的附生`生物分别进行区域丰度统计,附生生物在背壳的第3分区丰度最高,达到334个,除去仅3个腕足类别具有的第24分区外,腹壳的第17、21分区丰度最低,分别为58个和56个。无论按照何种类别进行统计,结果均显示结壳的分布主要集中在5个区域,丰度由高到低依次为I,II,III,V和IV。尽管整体规律十分明显,但不同的腕足类群与附生生物类群之间的分布依然存在差别。

-

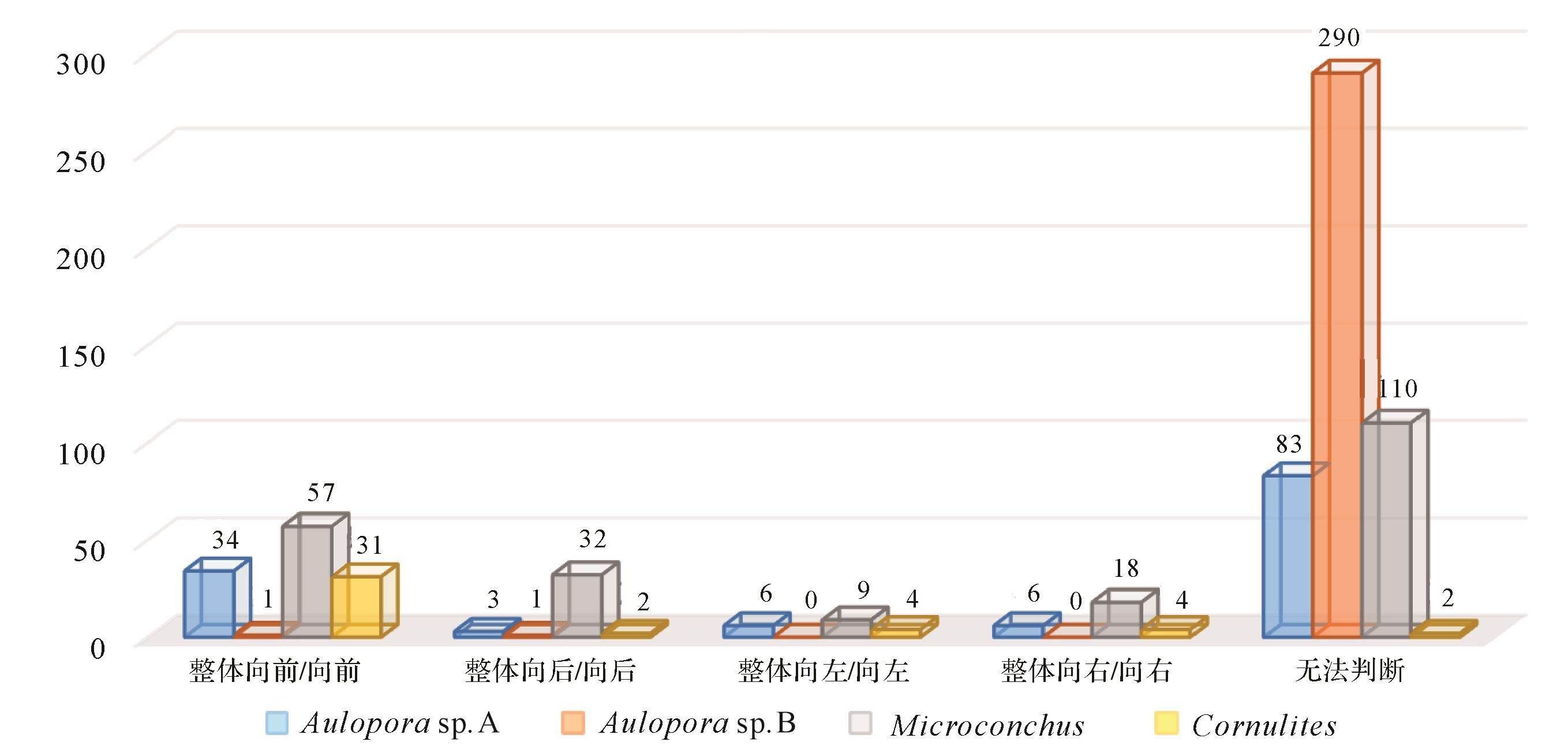

研究中多数的附生生物在宿主壳体上表现出不同程度的定向分布特征,如Aulopora sp.A,Aulopora sp.B,Microconchus,Cornulites以及四射珊瑚。统计结果如图6所示,定向性最明确的附生生物是Cornulites,仅有2个个体因化石保存不完整无法判断其萼部方向,其余个体定向明确,且多达31个个体萼部朝向壳体前部生长。而Aulopora sp.B定向性最差,仅有2个腕足类壳体上的Aulopora sp.B整体向前或向后,其余290个壳体无法判断其方向。Aulopora sp.A生长方向较Aulopora sp.B更有规律,34个壳体上的Aulopora sp.A整体向前,83个无法判断。Microconchus虽然容易判断其口径朝向,但各个方向均有分布,向前的个体较多。

3.1. 鉴定与特征描述

3.2. 附生生物在宿主背腹壳上的分布

3.3. 附生生物在不同分区间的分布差异

3.4. 附生生物各类群生长方向差异

-

附生生物在宿主壳体上的位置分布可以提供多种古生态信息,包括宿主的生活状态、附生生物与宿主之间的关系以及古生态环境等方面的证据[14⁃15,24⁃25]。

前人研究表明,泥盆纪石燕类和无洞贝类上所附着的喇叭孔珊瑚、枝状苔藓虫和Cornulites显示出较明显的方向性,即沿着或朝向两壳前端接合处生长[1,52⁃55]。本研究中所有的四射珊瑚都生长在壳体前缘,萼部朝向两壳接合处。有的个体数次改变生长方向,说明其除了依靠宿主腕足吸入的水流外,很可能还受到了动荡的海底环境影响,宿主位置改变使得其生长方向发生改变。而喇叭孔珊瑚Aulopora sp.A与Aulopora sp.B在宿主壳体上的分布显示出明显差异。Aulopora sp.A在腕足类两壳上丰度几乎一致,但Aulopora sp.B大多数生活在背壳上。这主要取决于宿主的生活状态,Aulopora sp. A主要附生于垂直底栖的石燕贝类,Aulopora sp.B的宿主则以成年后腹壳接触基底的无洞贝类为主。在萼部的取向上,Aulopora sp.A除了杂乱无法判断方向的标本外,大部分的萼部都沿着或朝向两壳前端接合处生长(图6)。而Aulopora sp.B在宿主壳体上没有明确的生长方向,细小的萼部之间经常充满泥质使得萼部沿垂直壳体方向伸展(图3i)。Chang et al.[25]对宿主死亡后仍在生长的附生生物进行了统计,结果显示少数Aulopora sp.A在宿主死亡后能够在短时期内存活,但Aulopora sp.B经常包裹宿主直至宿主死亡后仍在生长。因此,Aulopora sp.A的生存更依赖于腕足类宿主活体吸入或排出的水流,而对于Aulopora sp.B,腕足类宿主可能仅作为易得的硬底基质。

Microconchus和Cornulites属于多毛类管虫,是滤食性动物,通常将虫管附着在坚硬的基质上[56]。但是由于外壳形态的不同,导致其与腕足类宿主之间的关系也完全不同。Microconchus在宿主壳体各个分区上丰度差异不大(图5b),其螺旋状虫管亦没有明显的取向(图6),大多数虫管没有明显取向或向上延伸,通常附着在腕足类壳褶的凹槽中,这可能表明Microconchus不需要依靠宿主进水或排泄物,而是从周围水流中进行滤食,腕足类宿主只为其提供硬质基底以及作为庇护所,因此它们之间只是伴生关系。与Microconchus不同,66%的Cornulites附生在腕足类宿主的腹壳上(图4b),由于个体较大,壳体前部的所有区域(I,II,III,V和IV)都显示有Cornulites分布(图5b),但其虫管口均靠近两壳接合处;另一方面,与Microconchus一样,Cornulites也喜欢附着在壳褶之间的凹槽中,Cornulites的分布位置表明腕足类宿主不仅为它们提供了理想的硬底与庇护所,同时宿主的摄食水流也为其带来了食物,因此Cornulites很可能是腕足类宿主的寄生生物[55,57]。

腕足类的产出情况对于沉积环境也具有一定的指示作用。观雾山组产出了死亡后双壳张开保存的Independatrypa lemma和两壳微张的Uncinulusheterocostellis,这是快速或瞬时埋藏的标志。并且,115个腕足壳体死后仍有附生生物生长,其中以弗拉斯期土桥子组Leiorhynchus sp.,以及法门期的茅坝组Cyrtiopsis sp.、Cyrtospirifer sp.为主,说明腕足动物死后有充足的时间供附生生物生长。

综上所述,对于7种腕足类宿主而言,腕足动物壳体靠近喙部与主端的分区附生生物丰度都较低,原因可能是其直立底栖时喙部和主端后部靠近底质,附生生物很难附着。此外,附生生物在宿主背壳与腹壳上丰度大小主要与宿主腕足动物的生活方式有关,躺卧或者直立的生活状态可极大地影响附生生物的丰度。另一方面,附生生物在各分区的丰度和生长方向则与附生生物的生活类型(如伴生还是寄生)直接相关。

宿主与结壳生物之间关系的研究可拓展到多个方面,例如,可开展结壳生物在宿主上的多样性和丰度变化在不同地理区之间的对比研究,开展同一地区不同时间间隔的纵向上的演变研究,其研究结果对恢复沉积环境、古生态和底栖群落的演替等方面,都具有一定的指示意义。笔者最近发表了有关此方面的研究成果[25],揭示了泥盆纪末的F-F生物灭绝事件并没有显著降低由结壳生物与宿主之间表达的生态多样性。由于这方面的研究工作,在国内尚不多见。为方便读者理解,已发表文章的部分内容如样品信息、地质背景、部分研究方法等与本文有所重复,特此说明。

分区 I.lemma U.heterocostellis Leiorhynchus sp. Spinatrypina sp. A.beta Cyrtiopsis sp. Cyrtospirifer sp. 1 49 74 3 42 5 11 28 2 63 122 11 60 10 14 32 3 77 123 8 67 8 17 34 4 66 131 5 50 11 16 36 5 54 83 2 44 3 6 28 6 47 54 2 38 4 7 15 7 67 96 6 45 7 10 20 8 82 111 5 45 8 13 27 9 72 104 3 45 6 10 26 10 49 71 2 39 2 0 13 11 38 31 0 27 2 1 16 12 17 26 1 15 0 7 32 13 25 36 2 21 6 15 33 14 31 48 5 26 3 15 42 15 25 31 0 17 4 14 36 16 18 14 1 12 2 6 25 17 9 9 0 12 1 8 19 18 12 13 2 9 1 9 21 19 20 19 3 12 4 6 33 20 13 10 0 10 2 7 24 21 14 15 0 8 1 3 15 22 15 13 1 9 1 6 24 23 9 61 13 1 0 12 25 24 0 0 0 0 1 1 9 分区 Aulopora sp. A Aulopora sp. B 四射珊瑚 无铰纲腕足 Microconchus Cornulites 变口目苔藓虫 Allonema 1 40 136 1 7 8 0 14 6 2 59 195 1 5 23 3 19 7 3 59 204 1 9 23 2 18 18 4 55 191 5 10 19 2 20 13 5 32 141 3 4 14 0 18 8 6 22 111 0 7 5 0 11 11 7 36 160 0 9 13 2 13 18 8 44 186 0 10 19 2 14 16 9 35 180 0 13 10 1 12 15 10 13 124 2 3 8 3 10 13 11 14 74 0 2 9 0 11 5 12 34 42 0 2 5 1 10 4 13 44 56 2 2 15 4 10 5 14 49 67 1 9 20 3 13 8 15 40 50 1 3 12 3 15 3 16 27 34 0 5 1 1 8 2 17 22 20 0 4 4 0 6 2 18 24 24 0 2 9 2 4 2 19 28 33 0 6 18 3 5 4 20 25 24 0 3 7 1 5 1 21 14 23 0 4 4 2 6 3 22 25 23 0 2 8 3 5 3 23 46 38 0 1 9 6 17 4 24 10 0 0 0 1 0 0 0

DownLoad:

DownLoad: