HTML

-

鄂尔多斯块体周缘的新生代陆内伸展是欧亚大陆新生代变形的重要组成部分[1⁃4]。早始新世以来鄂尔多斯块体周缘就已出现一系列盆地,这些盆地的发育通常被认为与青藏高原的演化有关[1,5⁃8]。山西地堑系位于鄂尔多斯块体东缘,是块体周缘形成最晚的盆地系统 [9⁃11]。前人通过低温热年代学[12⁃17]和断层运动学分析[9,18⁃20]揭示了山西地堑系晚白垩世以来的主要构造事件。然而由于低温热年代学退火温度的限制以及断层运动学中剖面露头的局限,对晚中新世以来的盆地演化过程认识仍然不足。另一方面,已有的详细沉积学研究主要来自有限的和不完整的露头[21⁃25],这显然不足以对盆地演化进行深入理解。因此,完整的盆地地层资料仍然不足,而基于完整沉积序列和沉积环境演化的分析在盆地演化研究中至关重要[26]。

由于露头所揭露地层的局限性,为了获得太原盆地完整的沉积序列,我们在盆地东部开展了ZK01钻孔工作。本文通过对钻孔岩心所揭露的地层进行了沉积环境和物源分析,探讨了盆地的演化过程,并进一步讨论了气候变化和构造活动对盆地沉积环境演化的控制作用。这有助于更深入地认识山西地堑系在晚新生代中国东部构造体系中的角色和作用。

-

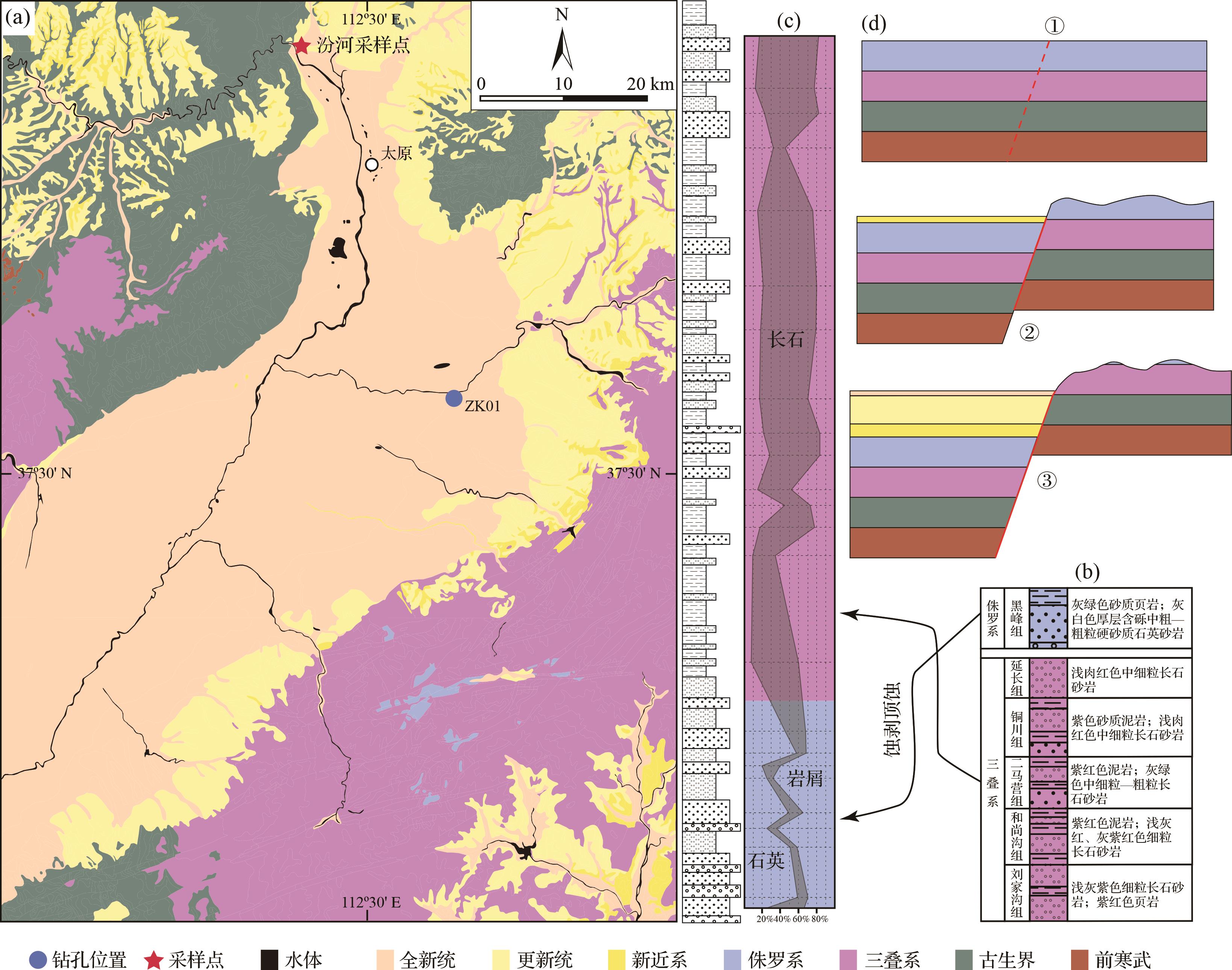

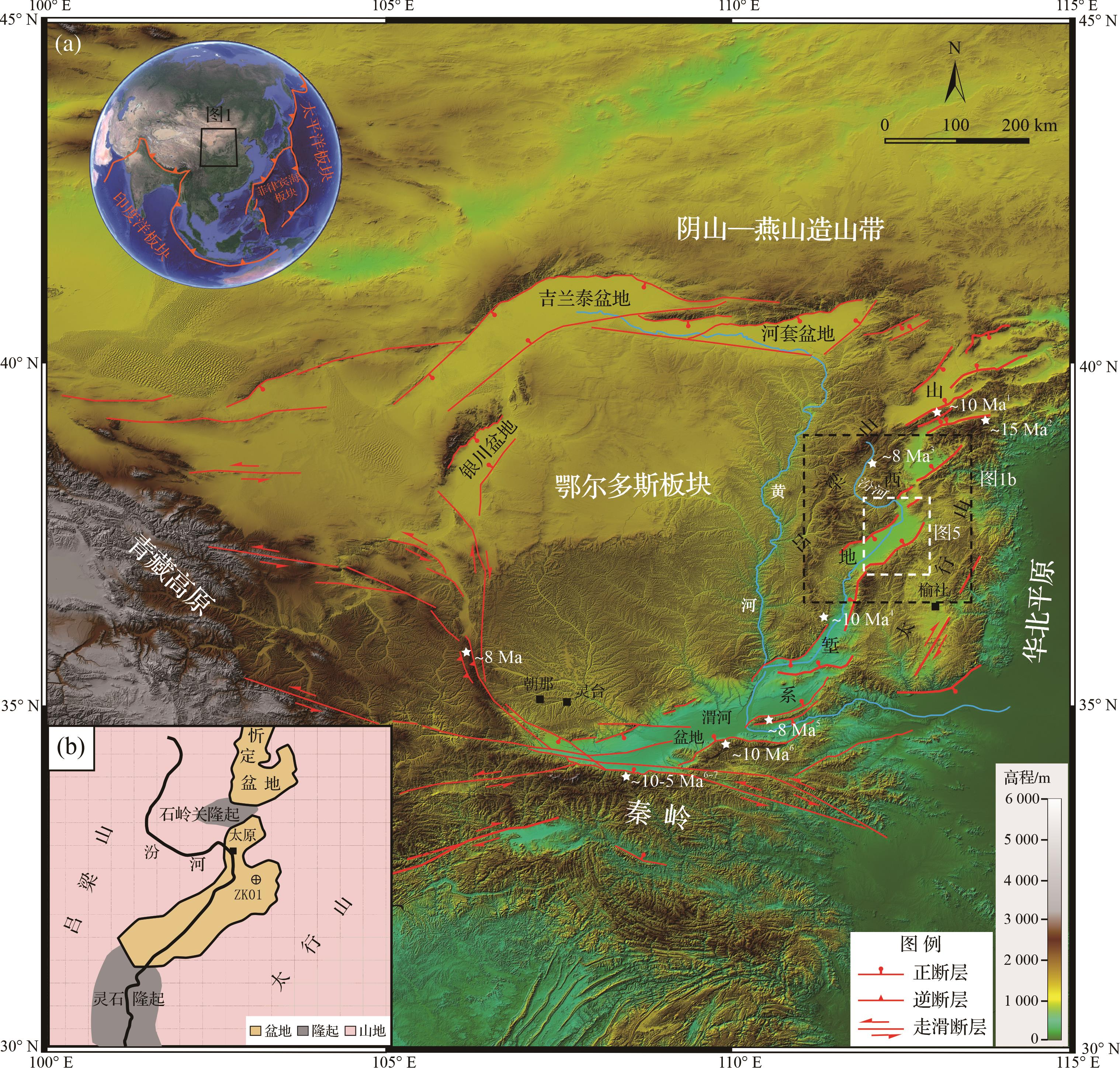

山西地堑系位于鄂尔多斯盆地东缘、华北平原西侧,分别由西侧的吕梁山和东侧的太行山相分隔(图1a)。地堑系在北部终止于阴山—燕山造山带,在南部与渭河盆地及秦岭山脉相连。依据前人钻孔资料[11,34⁃35]、风成红黏土和砾石沉积[36⁃37],以及新生代玄武岩发育[38⁃39],山西地堑系主要形成于晚中新世以来(<10 Ma)。低温热年代学数据[15,17,27⁃32]揭示山西地堑系周边地区最新一次快速冷却事件同样发生在大约10 Ma(图1a中白色五角星及时间标签)。地堑系从北向南一共5个盆地呈雁列状左阶排列(分别为大同盆地、忻定盆地、太原盆地、临汾盆地和运城盆地),延伸长度超过700 km[40]。盆地间被山脉或隆起相分隔[34,41]。盆山边界为山前陡倾断层,断层以倾滑为主,兼有少量右旋走滑分量[42⁃45]。活动的正断层控制着盆地的沉降,使新生代最大沉积厚度超过4 km[41]。前新生代地层构成了地堑系盆地周边山脉的主体。其中,太古代—古元古代火成岩和变质基底岩体,以及元古代低变质基底岩体主要出露于太原盆地北部和山西裂谷系最南部[46⁃47];而古生代海相—陆相地层和中生代河—湖相地层在区内分布广泛,占主导地位。在燕山期前新生代地层发生褶皱变形,形成北东—南西走向的太行山—吕梁山褶皱带[46]。此后,褶皱带被新生代地层所不整合覆盖。尽管一般认为盆缘断层是在晚新生代才开始活动[7,9,39],但盆地发育的位置和几何形态可能在一定程度上取决于先存的印支期(235~200 Ma)和燕山期(150~60 Ma)褶皱—逆冲构造[46]。

Figure 1. (a) Regional tectonic setting and digital elevation (SRTM 90 m resolution) of Ordos block and adjacent regions; (b) sketch of geology and geomorphology of Taiyuan Basin and adjacent regions

太原盆地位于山西地堑系中部,北西和南东向两条高角度正断层(交城断裂和太谷断裂)将盆地限制为菱形形态[34](图1b),东西两侧沉积物厚度的显著差异表明盆地为非对称式沉降[9,11,19],反映西侧的交城断裂比东侧的太谷断裂长期活动性更强。汾河发源于吕梁山北部,穿过交城断裂进入太原盆地,然后经过灵石隆起和临汾盆地,在临汾盆地西侧汇入黄河。汾河在吕梁山出山口前发育深切河曲。在太原盆地北端,石岭关隆起位于太原盆地和忻定盆地的结合处,由古生代灰岩和上覆的第四纪松散沉积物组成[39,47]。对石岭关隆起是否为滹沱河由忻定盆地进入太原盆地的古河道尚有很大争议[48⁃51]。在太原盆地南端,汾河通过狭长的灵石隆起进入临汾盆地,并在灵石隆起的古生代地层上切割出数百米深的峡谷。大部分新生代沉积物埋藏于盆地中,深度达4 000 m[34,39]。而其残余露头主要分布在盆地东侧的山前台地,在西侧盆缘很少见[39],这可能与交城断裂的强烈活动有关。太原盆地古地磁年代学揭示最底部沉积物年龄约8.1 Ma[11],标志着晚中新世沉积开始发育。

-

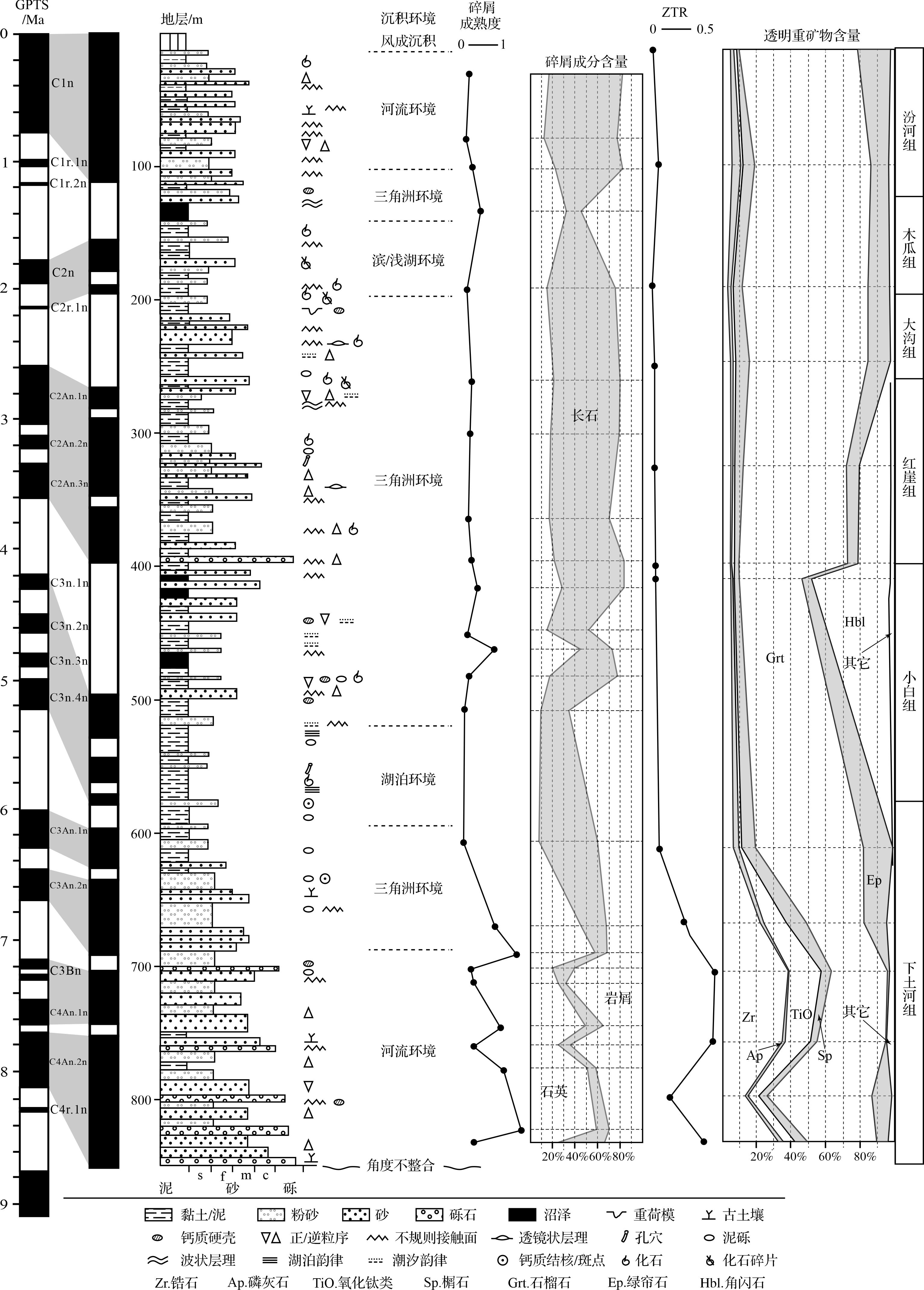

ZK01钻孔位于太原盆地东北部(112°40′11″ E,37°35′39″ N,图1b),岩心总长850 m,揭露出太原盆地完整的新生代地层序列。地层从底到顶划分为六个沉积组,分别为下土河组、小白组、红崖组、大沟组、木瓜组和汾河组(表1)。

年代地层 磁性地层 岩石地层 系 统 阶 GPTS2012年龄/Ma 组 厚度/m 第四系 全新统—中更新统 全新统—周口店阶 0~0.78 汾河组 127 下更新统 泥河湾阶 0.78~2.15 木瓜组 55 2.15~2.58 大沟组 82 新近系 上新统 麻则沟阶 2.58~3.60 红崖组 135 高庄阶 3.60~5.33 小白组 185 中新统 保德阶—灞河阶 5.33~8.11 下土河组 269 Table 1. Stratigraphic division of core ZK01

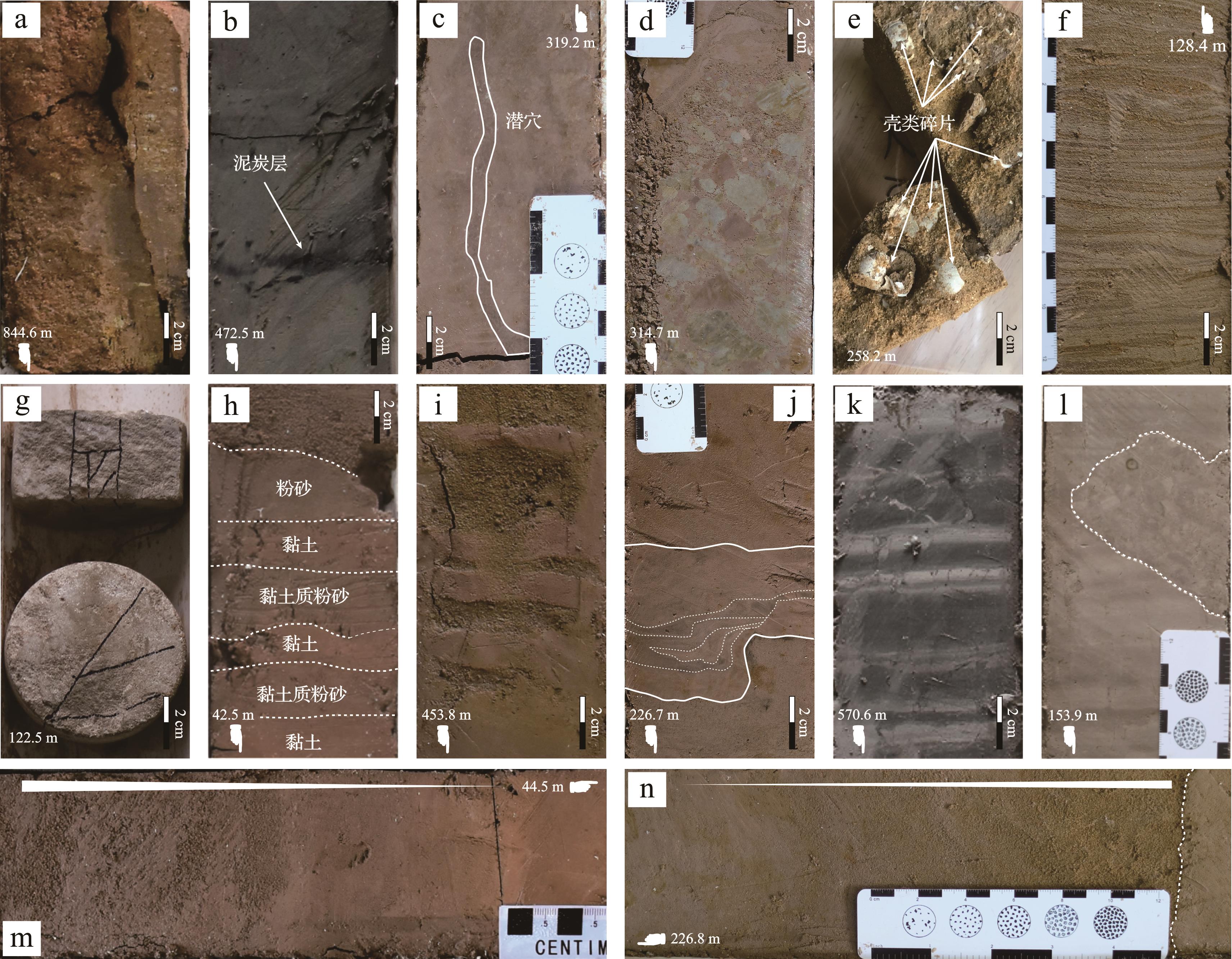

下土河组(853~584 m):不整合覆盖于上三叠统延长组上。下部(853~788 m)以棕色砾石和砂互层为特征。在粗粒部分的底部常见侵蚀面构造。砾石以中砾为主,磨圆中等—好,砾石成分主要为砂岩。砂从粉砂到粗砂不等,分选差。值得注意的是,在砾石层之间发育古土壤夹层(图2a)。沉积物颗粒大小向上减小,形成细砾—粉砂序列。上部(788~584 m)为块状浅砖红色粉砂和黏土质粉砂,含少量薄黏土夹层。粉砂粒径均一,富含钙质团块。这些沉积物被氧化铁染成了淡红色。此外,常见泥屑,意味着存在高能量流。化石少见。

小白组(584~399 m):小白组下部(584~508 m)是整个钻心中粒度最细的部分,大部分为灰白色—灰绿色黏土;上部(508~399 m)为深灰绿色黏土和淡棕色粉砂至粉砂质黏土,黑色富有机质黏土层出现在该段上部(图2b)。总体而言,该组呈现出向上变粗的趋势。小白组沉积物由于含有大量的碳酸钙而呈现浅灰色,与下伏的浅砖红色下土河组有明显的区别。小白组大部分为块状厚层,夹少量细层韵律层。常见生活在淡水中的蚬类碎片。

红崖组(399~264 m):红崖组沉积物粒径变化大。底部(399~338 m)为具正粒序的含砾中砂,上覆褐色块状黏土—粉砂质黏土。中部(338~320 m)为暗褐色粉砂—中砂与粉砂质黏土互层。粉砂质黏土中发育大量锈色的斑点。在该段的顶部,粉砂中可见垂直于层理的被泥土充填的居住洞穴(图2c)。这部分构成了红崖组中粒度最粗的部分。上部(320~264 m)由灰褐色粉砂和黏土组成。在黏土层中可以观察到黄绿色斑点。粉砂层中夹有一层10 cm厚的中砾石状泥屑。泥屑分选差,半棱角状,层面不规则(图2d)。红崖组中包含少量田螺化石。

大沟组(264~182 m):大沟组底部(264~246 m)以灰褐色、深褐色粉砂质黏土为主,发育薄层不显著的交错层理。可见大量的壳类碎片。粗粒部分(246~215 m)主要为棕色细砂和粉砂。砂质纯净、均一,常见显著的正粒序,也可见零星分布的磨圆良好的细砾石。正粒序层的底部常见侵蚀面构造。上部(215~182 m)由浅棕色粉砂和粉砂质黏土组成,夹少量薄层细砂。该段可见大量的黄绿色斑点、条纹和团块。薄层粉砂和黏土互层发育层状构造,这可能与气候变化有关。粉砂层通常呈透镜状,且底部界线截然,在其上表面呈现波纹。粉砂中可见大量的壳类碎片(图2e)。

木瓜组(182~127 m):木瓜组主要由棕色—灰黑色黏土和粉砂质黏土组成。大量破碎的贝壳散布在非常薄的细砂层中。在下部(172~173 m),大量的锈斑覆盖了粉砂质黏土。平行层理非常发育,尤其是在粒度最细的层位。在木瓜组上部,灰色黏土单元中常见黑色富有机质条带。顶部砂层发育波状层理(图2f)。

汾河组(127~0 m):棕色和灰褐色粉砂质黏土、粉砂和细砂是汾河组的主要特征。汾河组含砂量的显著增加与下伏以黏土和粉砂质黏土为主的木瓜组有明显差异。从木瓜组最上部深灰色黏土向汾河组最下部粉砂质黏土的转变是过渡的。在汾河组下部(127~118 m)出现坚硬而致密的白色钙质胶结物(图2g)。中部(118~18 m)交替出现浅棕色粉砂质黏土—粉砂和深棕色细砂—中砂。沉积物多为块状,常见冲刷充填构造。粉砂和砂层中偶见次棱角状细砾石。该段的顶部可见蚬类壳体碎片。汾河组的顶部(18~0 m)主要由粉砂和黏土组成,由于与非常细粒的黄土混合,沉积物特征混乱和模糊,未作进一步区分。

-

基于详细的钻孔岩心编录建立地层柱状图,并从沉积物的结构、沉积构造、颜色、化石等方面对沉积环境进行综合评价。由于钻孔岩心横向揭露的沉积物极为有限,一些大型沉积构造以及沉积层几何形态信息可能不完整甚至缺失,准确判断其所处沉积环境存在困难。因此,对具有特征性沉积环境指示意义的标志予以特别关注。如指示长期暴露风化环境的古土壤、河道滞留沉积砾石,以及湖滨潮汐层理等,确保沉积环境划分的准确性。

-

在ZK01钻孔中共计取了24个砂样进行碎屑成分识别和统计,每个样品重1~1.5 kg,砂样粒径为细粒到中粒。应用Gazzi-Dickinson方法[52⁃53],每个样品制作一个薄片统计至少300颗粒,在显微镜下鉴定其成分。

-

总计采集了14个重矿物样品,其中ZK01孔13个,汾河太原西山出山口处河滩1个。每个样品大约重1 kg。将样品充分分散后,筛选0.063~0.125 mm粒径的重矿物样,以尽可能降低水动力效应的影响[54⁃55]。然后使用三溴甲烷分离提取重矿物,并用酒精反复冲洗干净,烘干后在显微镜下鉴定。每个样品用条带计数法[56]随机选取500粒[57]重矿物颗粒,依据《地质矿产实验室测试质量管理规范》(DZ/T 0130—2006)鉴定其矿物类型。

3.1. 沉积环境分析方法

3.2. 物源分析方法

3.2.1. 碎屑成分

3.2.2. 重矿物

-

重点从沉积物的结构、构造、颜色、化石等方面对沉积环境进行综合评价。将太原盆地沉积环境划分为河流环境、三角洲环境和湖泊环境。

-

钻孔剖面的河流沉积环境主要发育在下土河组下部和汾河组。其中下土河组下部(690~853 m)的河流沉积以砾石、(含砾)粗砂为典型特征,汾河组的河流沉积为(含砾)细—中砂与下土河组相区别。

在下土河组底部(839~853 m)发育大量由次圆中砾石组成的河道滞留沉积,其底部发育冲刷面,砾石层之上覆盖中—粗砂。砂体以浅棕红色为主色调,反映地表氧化环境;砂体结构成熟度低,表现为分选差、杂基含量高,反映快速堆积过程;砾石层间夹古土壤层(图2a),表明长期暴露风化环境。该段向上(690~853 m)主要为块状和具正粒序中—粗砂与粉砂互层,局部夹薄层黏土。中粗砂层底面通常为侵蚀面,指示废弃河道的充填沉积,黏土为洪水末期悬浮沉积[58]。下土河组下部整体缺乏化石及生物遗迹构造,粉砂和黏土含量低,符合冲积扇—砂质辫状河沉积环境。但钻进作用导致砾石变位、旋转和破碎,并破坏了砾石层间的部分砂体,因此难以准确划分下土河组冲积扇与辫状河环境的界线,在此将其统一划分为河流环境。

汾河组(18~103 m)以具冲刷充填构造的细—中砂和上覆的粉砂质黏土—粉砂为特征,相比下土河组下部粗粒沉积物显著减少,层厚也显著减薄,而细粒沉积物比例显著提高。薄层泥和粉砂的互层为天然堤沉积(图2h)[59⁃60];而厚层黏土和粉砂构成泛滥平原沉积;由于泛滥平原沉积物累积速率缓慢,中部古土壤层反映沉积速率缓慢的泛滥平原沉积[61];在厚层细粒沉积中夹逆粒序砂(图2m),为被泛滥平原沉积所包裹的决口扇沉积[62]。这些特征表明该段为曲流河环境,但是钻孔位置远离主河道,位于泛滥平原中。这种沉积特征与观察到的现今汾河泛滥平原一致,均表现出成熟、稳定的河流性质。

-

三角洲环境分为三角洲平原、三角洲前缘和前三角洲亚环境。

三角洲平原沉积。三角洲平原处于河流与湖泊的过渡带,三角洲平原可以遵循河流的识别特征,但比河流沉积物粒度更细,规模更小,主要由砂、粉砂和泥组成。下土河组上部发育较多泥砾,表明洪水对天然堤或泛滥平原暴露沉积的冲刷作用[63](图2d)。小白组的黑色富有机质层解释为三角洲平原边缘分流间湾的沼泽环境沉积[62,64];泛滥平原沉积广泛发育,常见决口扇成因逆粒序砂;此外,钙质硬壳层(钙结层)被包裹在松散沉积物中,它们是半干旱气候下长时间在地面风化环境中形成的[62],一般出现在河道或三角洲环境中[65]。与丰富的侵蚀构造、古土壤和地层中向上变细的砂层(图2n)共同构成三角洲平原环境。

三角洲前缘沉积。三角洲前缘沉积位于河口前缘,沉积物受波浪和潮汐作用影响较大[62]。因此,小白组中由薄层粉砂和泥夹层组成的波状层理和潮汐韵律层(图2i)是三角洲前缘沉积的重要识别标志。破碎贝壳的出现(如红崖组顶部和大沟组顶部,图2e)代表了高能量环境,比如遭受湖浪冲击的湖滩[66]。红崖组上段中发育的软沉积变形(图2j)代表三角洲前缘的斜坡环境,当未固结沉积物受到地震等因素而振动时,就会出现扭曲变形层[67]。

前三角洲沉积。前三角洲是三角洲环境的最远端部分,与湖相沉积物相似,都具有块状和水平层理的特征(如木瓜组下部)。然而,与湖泊相比,前三角洲沉积有更多的粉砂和更少的黏土(如下土河组上部与小白组)。

-

在钻孔岩心中,将厚层块状泥解释为湖相沉积,而带有侵蚀底部的薄夹层粉砂则解释为水下水道沉积,在洪水或地震活动期间深入到湖泊深处[67]。具湖相沉积特征的层位主要为小白组下部和木瓜组下部。韵律岩是深湖相最具特征的沉积构造,由淡色的富碳酸盐岩和深色的富有机质层组成(图2k)。小白组沉积物的灰绿色也表明沉积为还原环境,稳定的韵律层和厚层黏土层表明小白组为较深的湖相沉积[68];而木瓜组下部包含大量侵蚀构造和壳类碎片,表明湖泊较浅,甚至木瓜组湖相沉积与前三角洲沉积难以区分。此外,木瓜组还发育破碎后原地沉积的深、浅色薄互层黏土碎屑,可能为风暴或地震成因(图2l)。

综上所述,将ZK01沉积环境划分为河流沉积环境、三角洲沉积环境和湖泊沉积环境(图3)。表现为河流—三角洲/湖泊—河流的沉积环境演化过程。

Figure 3. Sedimentary column and division of sedimentary environments of core ZK01 (paleomagnetic age from reference [11])

-

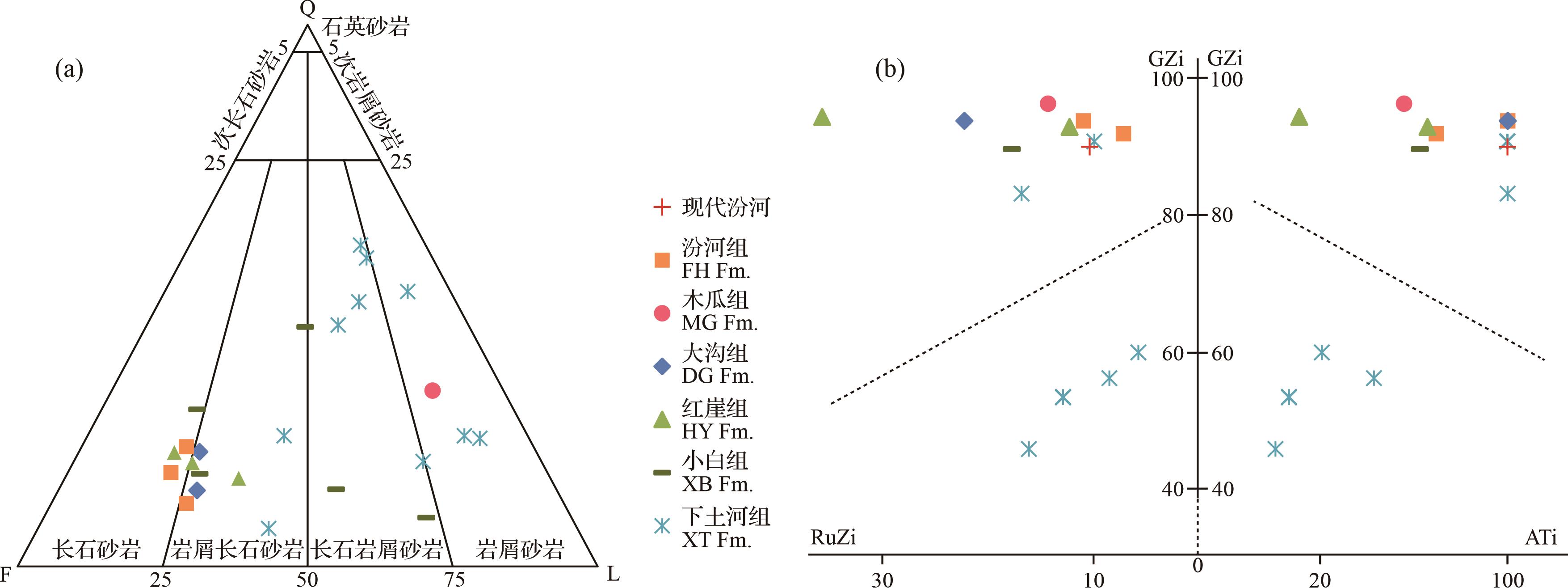

碎屑成分(表2)主要为石英(Q,单晶和多晶颗粒),长石(F,钾长石和斜长石)和岩屑(L,火山岩屑、沉积岩屑、硅质岩屑、碳酸盐岩岩屑和硅酸盐岩岩屑的集合体)。副矿物包括云母和含量较低的锆石、磁铁矿等重矿物。样品矿物含量差异较大,说明砂样的类型复杂。

样品编号 石英 长石 岩屑 云母 重矿物 Q-F-L分类 成熟度 斜长石 钾长石 Q% F% L% D28 46 73 99 47 41 7 17 65 18 0.21 D77 34 118 65 65 9 4 12 65 23 0.14 D98 65 73 103 53 10 19 22 60 18 0.28 D131 92 27 8 157 55 6 32 12 55 0.48 D190 37 103 65 65 13 5 14 62 24 0.16 D259 63 79 95 61 20 19 21 58 20 0.27 D298 57 83 101 63 19 7 19 61 21 0.23 D362 51 73 97 96 17 21 16 54 30 0.19 D393 57 74 97 45 12 27 21 63 16 0.26 D414 79 63 87 45 13 21 29 55 16 0.41 D449 36 54 41 120 36 2 14 38 48 0.17 D460 122 36 42 75 11 26 44 28 27 0.80 D480 45 75 84 60 20 4 17 60 23 0.21 D505 24 39 28 175 31 4 9 25 66 0.10 D605 21 87 68 116 43 1 7 53 40 0.08 D668 132 39 26 97 13 1 45 22 33 0.81 D689 167 22 11 93 7 1 57 11 32 1.33 D700 60 27 34 180 10 3 20 20 60 0.25 D710 77 18 9 218 3 1 24 8 68 0.31 D744 131 14 31 93 44 7 49 17 35 0.95 D758 66 9 21 179 24 4 24 11 65 0.32 D776 146 8 14 121 12 8 51 8 42 1.02 D821 165 11 21 83 16 3 59 11 30 1.43 D830 65 74 39 91 32 4 24 42 34 0.32 Table 2. Detrital composition and content of core ZK01

根据Q-F-L三元图解(图4a),ZK01钻孔中的砂可分为长石砂岩、岩屑长石砂岩、长石岩屑砂岩和岩屑砂岩。砂碎屑类型与沉积组之间存在一定的规律性。下土河组组拥有Q-F-L三元关系中最高比例的石英(59%)和岩屑(68%)组分。相反,长石的最高比例(65%)出现在最顶部的汾河组。下土河组和木瓜组主要为岩屑砂岩和长石岩屑砂岩,红崖组、大沟组和汾河组样品主要为长石砂岩—岩屑长石砂岩。而中段的小白组被划分为岩屑长石砂岩和长石岩屑砂岩,位于长石砂岩和岩屑砂岩的过渡区域。总体来看,剖面下部长石含量明显降低,而石英和岩屑含量略有增加。

-

共识别出重矿物种类18种(表3)。重点对锆石、金红石、石榴石和电气石进行形态特征观察。其中锆石以浅粉色和玫瑰色为主,半自形柱状或次棱角柱状,表面光亮洁净。少量磨圆度较高,晶体表面可见浅坑和浅凹槽,反映长距离的搬运和风化作用。金红石以深红、暗红色为主,呈柱状或粒状,半透明,具金刚光泽或油脂光泽。石榴石主要为粉色和浅粉色,透明粒状,玻璃光泽。电气石为茶褐色,次滚圆柱状和粒状,玻璃光泽。

采样层位 现代汾河 汾河组 木瓜组 大沟组 红崖组 小白组 下土河组 样品名称 HM-FH-1 HM-ZK01-1 HM-ZK01-2 HM-ZK01-3 HM-ZK01-4 HM-ZK01-5 HM-ZK01-6 HM-ZK01-7 HM-ZK01-8 HM-ZK01-9 HM- ZK01-10 HM- ZK01-11 HM- ZK01-12 HM- ZK01-13 锆石 17 8 13 6 7 14 9 14 9 50 102 83 15 44 磷灰石 6 3 10 4 2 3 1 5 4 4 1 5 2 4 锐钛矿 0 2 3 1 2 3 2 2 2 28 27 21 6 5 金红石 2 1 1 1 2 2 5 3 1 3 20 12 3 4 白钛石 0 2 5 2 2 8 1 4 6 56 41 72 3 20 黄铁矿 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 重晶石 0 0 0 11 15 0 1 0 0 0 0 36 0 0 榍石 1 3 16 13 11 13 7 10 11 25 14 9 6 10 独居石 2 0 1 1 0 5 3 3 0 2 3 1 1 2 石榴石 131 119 153 155 103 173 148 123 88 74 85 93 73 55 电气石 0 0 3 2 0 1 2 2 0 6 3 12 0 3 绿帘石 19 33 24 29 21 25 17 20 25 31 3 1 15 9 辉石 30 0 0 1 2 0 0 4 1 0 1 0 0 0 角闪石 9 3 3 0 0 54 47 155 0 2 0 0 0 0 铬铁矿 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 7 0 0 钛铁矿 56 0 0 0 0 96 152 41 0 0 0 0 0 0 赤褐铁矿 148 306 170 274 301 75 71 89 257 218 195 148 167 161 磁铁矿 79 20 98 0 32 28 34 25 96 0 0 0 209 183 GZi 89 94 92 96 94 93 94 90 91 60 45 53 83 56 Ati 100 100 77 67 100 75 33 71 100 40 25 29 100 57 RuZi 11 11 7 14 22 13 36 18 10 6 16 13 17 8 ZTR 0.09 0.05 0.07 0.04 0.06 0.06 0.07 0.06 0.07 0.26 0.48 0.45 0.15 0.38 Table 3. Type and quantity of heavy minerals and their provenance indices from the modern Fen River and core ZK01

对透明矿物和非自生矿物重新进行含量统计,发现矿物含量在不同沉积组或沉积环境中变化较大(图3)。其中锆石和氧化钛类矿物主要集中在下土河组,并在下土河组顶部开始急剧减少。石榴石含量从下土河组到小白组略有增加,且总体含量较高(>30%),但是从红崖组开始含量进一步增加,最高可达70%。角闪石含量在大多数沉积组中含量极低,但在小白组和红崖组中却急剧增加,在小白组顶部达到45%。其他种类重矿物含量分布变化较小。总体看来,重矿物含量在下土河组和小白组之间变化明显,在其他层位相对稳定。

4.1. 沉积环境分析结果

4.1.1. 河流环境

4.1.2. 三角洲环境

4.1.3. 湖泊环境

4.2. 碎屑成分分析结果

4.3. 重矿物分析结果

-

太原盆地为一夹于太行山和吕梁山之间的狭长型盆地。现今沉积物主要通过汾河及发源于两侧山脉的河流和风搬运至盆地内堆积,然后部分沉积物再通过汾河被搬运出太原盆地,进入临汾盆地或其他下游盆地中。

代表超稳定组分的锆石、电气石和TiO2矿物在盆地底部下土河组的中、下段沉积物样品(HM-ZK01-9~13)中的含量大约占据了在整个盆地样品中含量的78%(表3)。其中被称为ZTR组合的锆石、金红石和电气石代表经历多次沉积循环后残留下的稳定组分,一般来自沉积岩物源区。利用ZTR指数((锆石+金红石+电气石)/透明重矿物)[69]对沉积物中重矿物成熟度进行判别,可以有效判断沉积物所经历的再循环过程和搬运距离。ZK01孔中ZTR指数在下土河组中、下段显著偏高(0.15~0.45),而下土河组上段及以上层位则不超过0.1(图3)。这反映下土河组中、下段沉积物经历了更多的再循环沉积过程,或者经历了更远的搬运距离,这与其较高的碎屑成熟度(图3)及其河流环境相符。

由于沉积物从源到汇的过程会受风化、水动力分选以及成岩作用的影响,使用GZi(100×石榴石/(石榴石+锆石))、RuZi(100×金红石/(金红石+锆石))和ATi(100×磷灰石/(磷灰石+电气石))三个矿物对指标以降低外在因素对重矿物物源信息的干扰[55,70]。结果表明(图4b),下土河组样品中有4个样品独立于其他沉积组的样品,表现出明显的物源差异性。下土河组另外2个样品没有表现出与其他沉积组的明显差异,这可能主要由于样品已经受到其他物源的影响,因为与其他沉积组样品最接近的为下土河组最顶部的样品(HM-ZK01-8),属于三角洲沉积和湖泊沉积高度融合部位。现代汾河样品与盆地内中、上部沉积具有同源属性。

下土河组中、下部作为太原盆地最底部、砂砾含量最高的层位,具有同裂谷沉积特征,代表裂谷发育时最早期沉积[11],应该为近源沉积。该段沉积物ZTR指数和碎屑成熟度均为最高,反映长距离搬运或再循环沉积来源,而其重矿物物源属性与现代汾河差异较大,因此可以排除汾河的远距离搬运成因。从区域地层分布上看,盆地东侧太行山残留少量中侏罗纪地层[71](图5a),岩性主要为石英砂岩、砾岩和砂质泥岩[46],可以提供下土河组中高含量的石英成分(图5b,c);而占据盆地东侧山脉绝大部分面积的三叠系主要为长石砂岩[46],与盆地内中、上部地层碎屑成分相符(图5b,c)。因此,推测盆地东侧的太行山脉经历了蚀顶剥蚀过程。裂谷发育初期地表被厚度达5 000 m的古生代和中生代沉积所覆盖[72],其中侏罗系为最新地层。盆地断陷开始后首先剥蚀最顶部的侏罗系,造成富含石英的碎屑物质首先被搬运至盆地内(图5d,①~②)。当侏罗系被剥蚀殆尽,下伏三叠系大面积出露,盆地内沉积物转为以富含长石碎屑为主图5d,③)。而盆地发育到一定程度后,古汾河水系将吕梁山内火山岩和变质岩碎屑搬运至盆地内堆积,也进一步造成长石和非ZTR重矿物的富集。

Figure 5. (a) Geological map of Taiyuan Basin and adjacent area (modified from reference [71]); (b) stratigraphic column of the Triassic⁃Jurassic; (c) detrital composition diagram of core ZK01; (d) schematic sedimentary models of Taiyuan Basin

-

太原盆地沉积可划分为3段,分别为底部的河流沉积、中部的湖相和三角洲沉积,以及顶部的河流沉积。底部的粗粒河流沉积代表了盆地裂陷初期快速沉降过程的响应。随着砾石向上转化为细砂和泥,中段沉积物粒度急剧减小,几乎没有厚层的砂砾石层,也缺乏典型的河流相层理,主要为湖相沉积和三角洲沉积。从木瓜组上部开始,湖泊沉积物最终被反映湖泊收缩的三角洲沉积物所覆盖,至汾河组湖泊退出,河流沉积再次占据主体地位。

来自钻孔岩心的三角洲沉积普遍为细粒沉积,与扇三角洲或辫状河三角洲沉积差别较大[73⁃75]。而陡倾斜前积层的缺失表明三角洲类型为缓坡细粒河流三角洲而非典型的吉尔伯特型粗粒三角洲。这也符合太原盆地为半地堑的盆地类型。钻孔位于盆地活动性较弱的一侧,坡度和沉降速率较低[76]。

根据韵律层和稳定黏土层的分布,在小白组下部和木瓜组下部可划分出两个大湖期(图3)。ZK01孔在5.8 Ma(584 m)沉积环境发生突变,从棕红色三角洲沉积到深色富有机质层的转变是突然的而非过渡的。深色有机质层和浅色钙质层标志深湖相沉积环境。沉积速率增大[11],反映湖泊扩张加快。在5.8~4.4 Ma形成一个覆盖整个盆地的湖泊。在这种裂谷盆地环境中,由于湖泊盆地边缘更陡峭,湖泊水位的垂直变化可能非常剧烈和迅速[77]。ZK01孔在第一次湖侵之后直到约2.2 Ma都是以三角洲平原和三角洲前缘交互沉积为主,未发育稳定的湖相沉积。而2.2 Ma开始的湖侵事件沉积厚度较薄、持续时间短,很快转变为三角洲及河流相沉积,其湖侵规模小于第一次湖侵。此后,未再发育典型湖相沉积,而是转为三角洲沉积,表明太原盆地湖泊逐渐萎缩。ZK01孔0.6 Ma之后三角洲环境转变为河流环境,湖泊已大幅萎缩直至完全干涸。因此,太原盆地晚新生代总共发育两次湖侵范围到达盆地东侧边缘,形成几乎覆盖整个太原盆地的超大湖期,分别为晚中新世—早上新世(约5.8~4.4 Ma)和早更新世早期(约2.2~1.6 Ma)。

-

陆相盆地的内部沉积结构最有可能受构造作用和气候变化的控制[76⁃77]。具体来说,湖泊是构造运动和湿润气候的产物[78]。本文尝试探讨气候和构造对太原盆地湖相演化的控制作用。

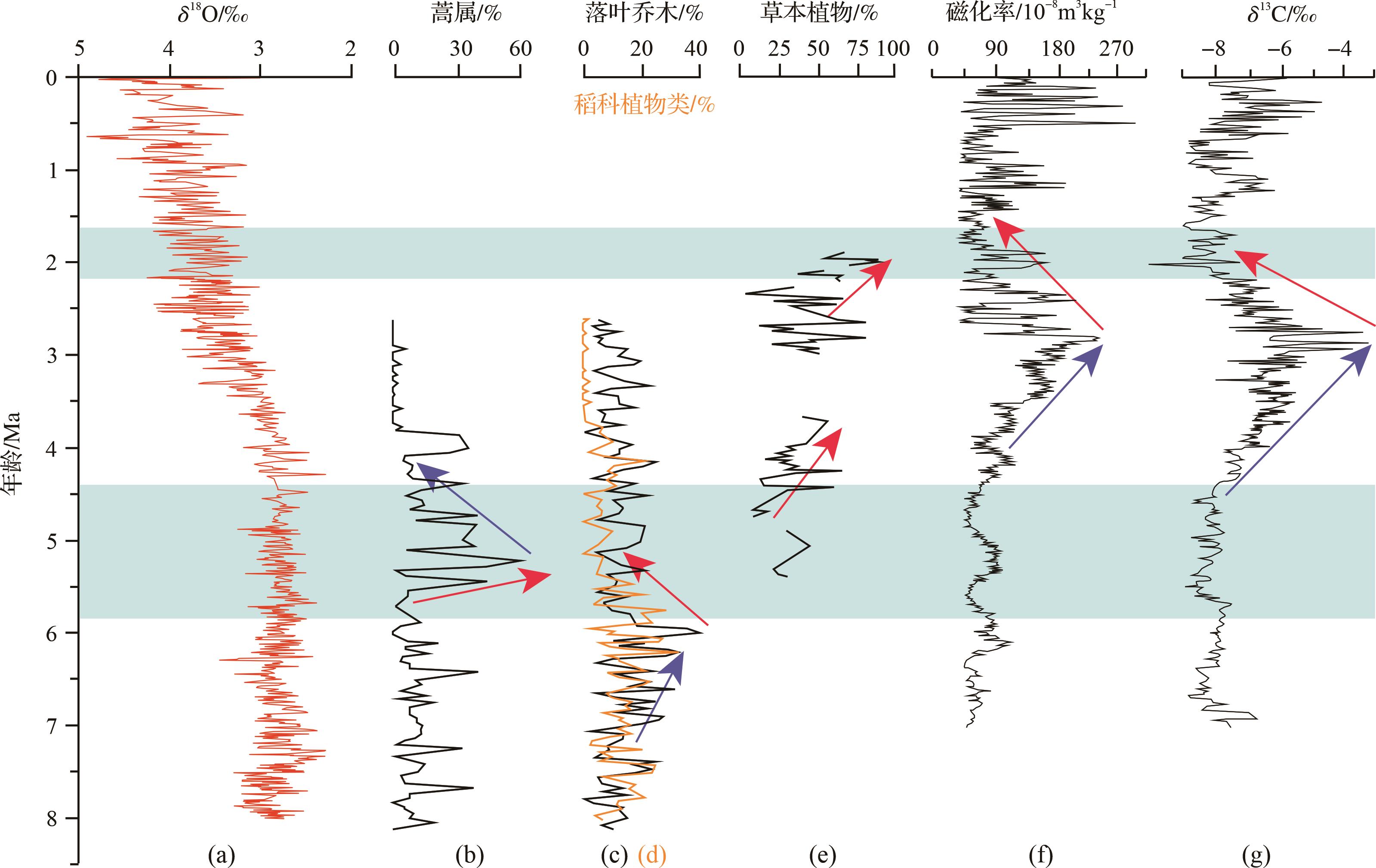

从区域气候环境来看,由于北半球海冰扩张[79]和青藏高原隆升[80⁃81],东亚在晚中新世以来经历了一个整体的变干和变冷的过程[82⁃84](图6a)。山西地堑系位于现今黄土高原东缘。根据黄土高原朝那剖面的磁性粒度记录[85]以及蒿属、落叶乔木和稻科的花粉记录[86],黄土高原在5.8~4.4 Ma期间并不特别湿润,甚至有干旱化趋势[86](图6b~d)。尽管有些研究认为夏季降水在这一时期由于夏季风增强而增加[87⁃88],但太原盆地夏季降水模拟表明大部分增加的降雨被太行山脉所阻挡,晚中新世和上新世夏季降水差异小于40 mm[89],这种量级的降雨增加显然不能对太原盆地的沉积环境产生决定性的影响。进入第四纪后季风增强,气候波动频繁且剧烈。2.6~1.8 Ma期间榆社盆地草本植物的花粉含量比例[90](图6e)和灵台地区的磁化率(图6f)和土壤碳酸盐δ13C[91](图6g)均表现出显著的干旱化趋势。这两个时期的气候均不利于湖泊的大规模扩张。因此,气候变化显然不是这两期超大湖泊形成的直接因素。

从区域构造背景来看,山西地堑系及周边区域在8~10 Ma经历了一次广泛的快速隆升过程(图1),推测山西地堑系的发育与该期区域构造事件吻合,而其发育时间也与太原盆地ZK01钻孔最底部沉积物的年龄一致[11]。而之后第一次湖侵与吕梁山5.7 Ma左右的快速隆升事件[92]时间一致,第二次湖侵与裂谷早更新世开始的构造应力的转变时间一致[19,93],这些构造事件均与青藏高原北东向扩展相关。

鄂尔多斯周缘盆地普遍发育多期大型湖泊,这些湖泊的发育和消亡往往是构造运动或者重大水系重组的直接反映。如吉兰泰—河套古湖的形成可能与12万年前共和运动造成的鄂尔多斯高原抬升阻碍黄河外流有关[94⁃95],而其消亡也可能与黄河在晋陕峡谷在北端的贯通有关[96]。因此,推测构造作用主导了太原盆地的湖泊演化。

太原5.8 Ma古大湖的形成可能是盆地快速沉降(约5.7 Ma吕梁山快速隆升[92])产生巨大的可容纳空间,以及因此导致的盆地与灵石隆起的差异抬升作用阻断了古汾河南流的结果;2.2 Ma古大湖的形成可能更多与早更新世NE—SW向伸展(早更新世构造应力转换[19,93])造成的灵石隆起与盆地的快速差异抬升作用有关。目前,灵石隆起北部汾河河谷两侧山区的平均海拔为1 100 m,远高于隆起以北的盆地南端750 m的平均海拔。尽管缺乏隆起和盆地的抬升速率的差异值,但二者之间具有显著的海拔差异这一事实表明灵石隆起具备阻挡古汾河进入临汾盆地的地质条件。灵石隆起之上晚新生代地层厚度可达600 m,在中段安乐村剖面和南坛剖面发育泥灰岩等典型湖相沉积,其中南坛剖面底部可见一套厚约8 m的湖相灰岩[39],反映灵石隆起之上曾发育湖泊。因此,我们推测太原盆地古湖泊在达到最大湖侵面后,湖水漫过灵石隆起向南溢流至临汾盆地,并在灵石隆起的低洼地段形成湖泊。溢流也导致灵石隆起在与临汾盆地边界处开始出现溯源侵蚀。随着溯源侵蚀的发展,逐渐形成连接太原盆地和临汾盆地的串联河流。同时,隆升作用使古汾河在灵石隆起上开始下切,而盆地也不断被沉积物充填,当河流下切至与盆地地表高度一致时,太原盆地古湖泊便被排空,汾河在太原盆地中重现并贯穿整个盆地。

5.1. 物源分析

5.2. 太原盆地沉积环境演化及其影响因素

5.2.1. 太原盆地沉积环境和古湖泊演化

5.2.2. 湖泊演化影响因素

-

(1) 太原盆地ZK01钻孔揭示出8.1 Ma以来河流—三角洲/湖泊—河流的沉积环境演化过程。物源分析表明早期物源主要来自东部太行山中生代砂岩,并揭示了盆地东侧太行山脉的蚀顶剥蚀过程;5.8 Ma开始的湖泊发育过程伴随着碎屑成分和重矿物组合的转变,来自吕梁山北部的变质岩和火山岩碎屑开始进入盆地。

(2) 在5.8~4.4 Ma和2.2~1.6 Ma分别发育两期覆盖整个太原盆地的超大湖泊。这两期湖泊扩展过程与区域古气候变化不同步,但能够与区域构造事件相关联,表明主要受控于构造过程。这两次构造过程同盆地的初始发育过程一样,均为青藏高原扩展过程在鄂尔多斯块体东缘的构造响应。

DownLoad:

DownLoad: